This is the memo of the 3rd course (5 courses in all) of ‘Machine Learning with Python’ skill track.

You can find the original course HERE .

#### KNN classification

In this exercise you’ll explore a subset of the

Large Movie Review Dataset

. The variables

X_train

,

X_test

,

y_train

, and

y_test

are already loaded into the environment. The

X

variables contain features based on the words in the movie reviews, and the

y

variables contain labels for whether the review sentiment is positive (+1) or negative (-1).

This course touches on a lot of concepts you may have forgotten, so if you ever need a quick refresher, download the Scikit-Learn Cheat Sheet and keep it handy!

X_train.shape

# (2000, 2500)

X_test.shape

# (2000, 2500)

type(X_train)

scipy.sparse.csr.csr_matrix

X_train[0]

<1x2500 sparse matrix of type '<class 'numpy.float64'>'

with 73 stored elements in Compressed Sparse Row format>

y_train[-10:]

array([-1., 1., 1., -1., -1., 1., -1., 1., 1., 1.])

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

# Create and fit the model

knn = KNeighborsClassifier()

knn.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Predict on the test features, print the results

pred = knn.predict(X_test)[0]

print("Prediction for test example 0:", pred)

# Prediction for test example 0: 1.0

#### Comparing models

Compare k nearest neighbors classifiers with k=1 and k=5 on the handwritten digits data set, which is already loaded into the variables

X_train

,

y_train

,

X_test

, and

y_test

.

Which model has a higher test accuracy?

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=1)

knn.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = knn.predict(X_test)

print(accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred))

# 0.9888888888888889

knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=5)

knn.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = knn.predict(X_test)

print(accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred))

# 0.9933333333333333

#### Running LogisticRegression and SVC

In this exercise, you’ll apply logistic regression and a support vector machine to classify images of handwritten digits.

X_train[:2]

array([[ 0., 0., 10., 16., 5., 0., 0., 0., 0., 1., 10., 14., 12.,

0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 9., 11., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.,

2., 11., 13., 3., 0., 0., 0., 0., 11., 16., 16., 16., 7.,

0., 0., 0., 3., 16., 4., 5., 1., 0., 0., 0., 7., 13.,

0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 13., 6., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 3., 11., 13., 15., 3., 0., 0., 4., 16., 14., 11.,

16., 8., 0., 0., 2., 5., 0., 14., 15., 1., 0., 0., 0.,

0., 0., 16., 11., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 11., 10., 0.,

0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 8., 12., 0., 0., 0., 0., 8., 11.,

15., 8., 0., 0., 0., 0., 2., 12., 14., 3., 0., 0.]])

y_train[:2]

# array([7, 3])

X_train.shape

# (1347, 64)

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.svm import SVC

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn import datasets

# load the data

digits = datasets.load_digits()

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(digits.data, digits.target)

# Apply logistic regression and print scores

lr = LogisticRegression()

lr.fit(X_train, y_train)

# score(self, X, y[, sample_weight])

# Returns the mean accuracy on the given test data and labels.

print(lr.score(X_train, y_train))

print(lr.score(X_test, y_test))

# 0.9955456570155902

# 0.9622222222222222

# Apply SVM and print scores

svm = SVC()

svm.fit(X_train, y_train)

# score(self, X, y[, sample_weight])

# Returns the mean accuracy on the given test data and labels.

print(svm.score(X_train, y_train))

print(svm.score(X_test, y_test))

# 1.0

# 0.48

Later in the course we’ll look at the similarities and differences of logistic regression vs. SVMs.

#### Sentiment analysis for movie reviews

In this exercise you’ll explore the probabilities outputted by logistic regression on a subset of the Large Movie Review Dataset .

The variables

X

and

y

are already loaded into the environment.

X

contains features based on the number of times words appear in the movie reviews, and

y

contains labels for whether the review sentiment is positive (+1) or negative (-1).

get_features?

Signature: get_features(review)

Docstring: <no docstring>

File: /tmp/tmpn52ffwy5/<ipython-input-1-33e0d8df8588>

Type: function

review1 = "LOVED IT! This movie was amazing. Top 10 this year."

review1_features = get_features(review1)

review1_features

<1x2500 sparse matrix of type '<class 'numpy.int64'>'

with 8 stored elements in Compressed Sparse Row format>

# Instantiate logistic regression and train

lr = LogisticRegression()

lr.fit(X, y)

# Predict sentiment for a glowing review

review1 = "LOVED IT! This movie was amazing. Top 10 this year."

review1_features = get_features(review1)

print("Review:", review1)

print("Probability of positive review:", lr.predict_proba(review1_features)[0,1])

# Review: LOVED IT! This movie was amazing. Top 10 this year.

# Probability of positive review: 0.8079007873616059

# Predict sentiment for a poor review

review2 = "Total junk! I'll never watch a film by that director again, no matter how good the reviews."

review2_features = get_features(review2)

print("Review:", review2)

print("Probability of positive review:", lr.predict_proba(review2_features)[0,1])

# Review: Total junk! I'll never watch a film by that director again, no matter how good the reviews.

# Probability of positive review: 0.5855117402793947

#### Visualizing decision boundaries

In this exercise, you’ll visualize the decision boundaries of various classifier types.

A subset of

scikit-learn

‘s built-in

wine

dataset is already loaded into

X

, along with binary labels in

y

.

X[:3]

array([[11.45, 2.4 ],

[13.62, 4.95],

[13.88, 1.89]])

y[:3]

array([ True, True, False])

plot_4_classifiers?

Signature: plot_4_classifiers(X, y, clfs)

Docstring: <no docstring>

File: /usr/local/share/datasets/plot_classifier.py

Type: function

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.svm import SVC, LinearSVC

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

# Define the classifiers

classifiers = [LogisticRegression(), LinearSVC(), SVC(), KNeighborsClassifier()]

# Fit the classifiers

for c in classifiers:

c.fit(X, y)

# Plot the classifiers

plot_4_classifiers(X, y, classifiers)

plt.show()

As you can see, logistic regression and linear SVM are linear classifiers whereas the default SVM and KNN are not.

#### Changing the model coefficients

# Set the coefficients

model.coef_ = np.array([[-1,1]])

model.intercept_ = np.array([-3])

# Plot the data and decision boundary

plot_classifier(X,y,model)

# Print the number of errors

num_err = np.sum(y != model.predict(X))

print("Number of errors:", num_err)

# Number of errors: 0

model.coef_ = np.array([[-1,1]])

model.intercept_ = np.array([-3])

model.coef_ = np.array([[-1,1]])

model.intercept_ = np.array([1])

model.coef_ = np.array([[-1,1]])

model.intercept_ = np.array([-3])

model.coef_ = np.array([[-1,0]])

model.intercept_ = np.array([-3])

model.coef_ = np.array([[-1,1]])

model.intercept_ = np.array([-3])

model.coef_ = np.array([[-1,2]])

model.intercept_ = np.array([-3])

model.coef_ = np.array([[-1,1]])

model.intercept_ = np.array([-3])

model.coef_ = np.array([[0,1]])

model.intercept_ = np.array([-3])

As you can see, the coefficients determine the slope of the boundary and the intercept shifts it.

#### Minimizing a loss function

In this exercise you’ll implement linear regression “from scratch” using

scipy.optimize.minimize

.

We’ll train a model on the Boston housing price data set, which is already loaded into the variables

X

and

y

. For simplicity, we won’t include an intercept in our regression model.

X.shape

(506, 13)

X[:2]

array([[6.3200e-03, 1.8000e+01, 2.3100e+00, 0.0000e+00, 5.3800e-01,

6.5750e+00, 6.5200e+01, 4.0900e+00, 1.0000e+00, 2.9600e+02,

1.5300e+01, 3.9690e+02, 4.9800e+00],

[2.7310e-02, 0.0000e+00, 7.0700e+00, 0.0000e+00, 4.6900e-01,

6.4210e+00, 7.8900e+01, 4.9671e+00, 2.0000e+00, 2.4200e+02,

1.7800e+01, 3.9690e+02, 9.1400e+00]])

y[:3]

array([24. , 21.6, 34.7])

from scipy.optimize import minimize

# The squared error, summed over training examples

def my_loss(w):

s = 0

for i in range(y.size):

# Get the true and predicted target values for example 'i'

y_i_true = y[i]

y_i_pred = w@X[i]

s = s + (y_i_true - y_i_pred)**2

return s

# Returns the w that makes my_loss(w) smallest

w_fit = minimize(my_loss, X[0]).x

print(w_fit)

# Compare with scikit-learn's LinearRegression coefficients

lr = LinearRegression(fit_intercept=False).fit(X,y)

print(lr.coef_)

[-9.16299112e-02 4.86754828e-02 -3.77698794e-03 2.85635998e+00

-2.88057050e+00 5.92521269e+00 -7.22470732e-03 -9.67992974e-01

1.70448714e-01 -9.38971600e-03 -3.92421893e-01 1.49830571e-02

-4.16973012e-01]

[-9.16297843e-02 4.86751203e-02 -3.77930006e-03 2.85636751e+00

-2.88077933e+00 5.92521432e+00 -7.22447929e-03 -9.67995240e-01

1.70443393e-01 -9.38925373e-03 -3.92425680e-01 1.49832102e-02

-4.16972624e-01]

not good for classification because loss is large on the correct predict

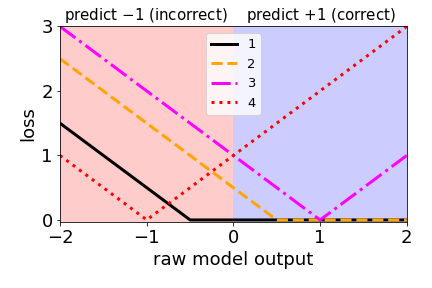

#### Classification loss functions

Which of the four loss functions makes sense for classification?

2.

This loss is very similar to the hinge loss used in SVMs (just shifted slightly).

#### Comparing the logistic and hinge losses

In this exercise you’ll create a plot of the logistic and hinge losses using their mathematical expressions, which are provided to you.

The loss function diagram from the video is shown below.

# Mathematical functions for logistic and hinge losses

def log_loss(raw_model_output):

return np.log(1+np.exp(-raw_model_output))

def hinge_loss(raw_model_output):

return np.maximum(0,1-raw_model_output)

# Create a grid of values and plot

grid = np.linspace(-2,2,1000)

plt.plot(grid, log_loss(grid), label='logistic')

plt.plot(grid, hinge_loss(grid), label='hinge')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

As you can see, these match up with the loss function diagrams above.

#### Implementing logistic regression

This is very similar to the earlier exercise where you implemented linear regression “from scratch” using

scipy.optimize.minimize

. However, this time we’ll minimize the logistic loss and compare with scikit-learn’s

LogisticRegression

(we’ve set

C

to a large value to disable regularization; more on this in Chapter 3!).

The

log_loss()

function from the previous exercise is already defined in your environment, and the

sklearn

breast cancer prediction dataset (first 10 features, standardized) is loaded into the variables

X

and

y

.

X.shape

(569, 10)

X[:2]

array([[ 1.09706398e+00, -2.07333501e+00, 1.26993369e+00,

9.84374905e-01, 1.56846633e+00, 3.28351467e+00,

2.65287398e+00, 2.53247522e+00, 2.21751501e+00,

2.25574689e+00],

[ 1.82982061e+00, -3.53632408e-01, 1.68595471e+00,

1.90870825e+00, -8.26962447e-01, -4.87071673e-01,

-2.38458552e-02, 5.48144156e-01, 1.39236330e-03,

-8.68652457e-01]])

y[:2]

array([-1, -1])

# The logistic loss, summed over training examples

def my_loss(w):

s = 0

for i in range(y.shape[0]):

raw_model_output = w@X[i]

s = s + log_loss(raw_model_output * y[i])

return s

# Returns the w that makes my_loss(w) smallest

w_fit = minimize(my_loss, X[0]).x

print(w_fit)

# Compare with scikit-learn's LogisticRegression

lr = LogisticRegression(fit_intercept=False, C=1000000).fit(X,y)

print(lr.coef_)

[ 1.03592182 -1.65378492 4.08331342 -9.40923002 -1.06786489 0.07892114

-0.85110344 -2.44103305 -0.45285671 0.43353448]

[[ 1.03731085 -1.65339037 4.08143924 -9.40788356 -1.06757746 0.07895582

-0.85072003 -2.44079089 -0.45271 0.43334997]]

minimize(my_loss, X[0])

fun: 73.43533837769074

hess_inv: array([[ 0.36738362, -0.00184266, -0.09662977, -0.38758529, -0.0212197 ,

-0.05640658, -0.03033375, 0.21477573, 0.01029659, -0.03659313],

...

[-0.03659313, -0.00862774, 0.09674119, 0.03706539, 0.02197145,

-0.16126887, 0.06496472, -0.09572242, 0.01406182, 0.0907421 ]])

jac: array([ 0.00000000e+00, 4.76837158e-06, 2.86102295e-06, 3.81469727e-06,

-4.76837158e-06, -2.86102295e-06, -6.67572021e-06, -9.53674316e-07,

9.53674316e-07, -7.62939453e-06])

message: 'Optimization terminated successfully.'

nfev: 660

nit: 40

njev: 55

status: 0

success: True

x: array([ 1.03592182, -1.65378492, 4.08331342, -9.40923002, -1.06786489,

0.07892114, -0.85110344, -2.44103305, -0.45285671, 0.43353448])

As you can see, logistic regression is just minimizing the loss function we’ve been looking at.

#### Regularized logistic regression

In Chapter 1, you used logistic regression on the handwritten digits data set. Here, we’ll explore the effect of L2 regularization.

The handwritten digits dataset is already loaded, split, and stored in the variables

X_train

,

y_train

,

X_valid

, and

y_valid

.

X_train[:2]

array([[ 0., 0., 7., 15., 15., 5., 0., 0., 0., 6., 16., 12., 16.,

12., 0., 0., 0., 1., 7., 0., 16., 10., 0., 0., 0., 0.,

0., 10., 15., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 1., 16., 7., 0., 0.,

0., 0., 0., 10., 13., 1., 5., 1., 0., 0., 0., 12., 12.,

13., 15., 3., 0., 0., 0., 10., 16., 13., 3., 0., 0.],

[ 0., 0., 0., 10., 11., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 3., 16., 10.,

0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 8., 16., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.,

12., 14., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 14., 16., 15., 6., 0.,

0., 0., 0., 12., 16., 12., 15., 6., 0., 0., 0., 7., 16.,

10., 13., 14., 0., 0., 0., 0., 9., 13., 11., 6., 0.]])

y_train[:2]

array([2, 6])

# Train and validaton errors initialized as empty list

train_errs = list()

valid_errs = list()

# Loop over values of C_value

for C_value in [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 1000]:

# Create LogisticRegression object and fit

lr = LogisticRegression(C=C_value)

lr.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Evaluate error rates and append to lists

train_errs.append( 1.0 - lr.score(X_train, y_train) )

valid_errs.append( 1.0 - lr.score(X_valid, y_valid) )

# Plot results

plt.semilogx(C_values, train_errs, C_values, valid_errs)

plt.legend(("train", "validation"))

plt.show()

As you can see, too much regularization (small

C

) doesn’t work well – due to underfitting – and too little regularization (large

C

) doesn’t work well either – due to overfitting.

#### Logistic regression and feature selection

In this exercise we’ll perform feature selection on the movie review sentiment data set using L1 regularization. The features and targets are already loaded for you in

X_train

and

y_train

.

We’ll search for the best value of

C

using scikit-learn’s

GridSearchCV()

.

# Specify L1 regularization

lr = LogisticRegression(penalty='l1')

# Instantiate the GridSearchCV object and run the search

searcher = GridSearchCV(lr, {'C':[0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10]})

searcher.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Report the best parameters

print("Best CV params", searcher.best_params_)

# Find the number of nonzero coefficients (selected features)

best_lr = searcher.best_estimator_

coefs = best_lr.coef_

print("Total number of features:", coefs.size)

print("Number of selected features:", np.count_nonzero(coefs))

Best CV params {'C': 1}

Total number of features: 2500

Number of selected features: 1220

#### Identifying the most positive and negative words

In this exercise we’ll try to interpret the coefficients of a logistic regression fit on the movie review sentiment dataset. The model object is already instantiated and fit for you in the variable

lr

.

In addition, the words corresponding to the different features are loaded into the variable

vocab

.

lr

LogisticRegression(C=1.0, class_weight=None, dual=False, fit_intercept=True,

intercept_scaling=1, max_iter=100, multi_class='ovr', n_jobs=1,

penalty='l2', random_state=None, solver='liblinear', tol=0.0001,

verbose=0, warm_start=False)

vocab.shape

(2500,)

vocab[:3]

array(['the', 'and', 'a'], dtype='<U14')

vocab[-3:]

array(['birth', 'sorts', 'gritty'], dtype='<U14')

# Get the indices of the sorted cofficients

inds_ascending = np.argsort(lr.coef_.flatten())

inds_ascending

# array([1278, 427, 240, ..., 1458, 870, 493])

inds_descending = inds_ascending[::-1]

inds_descending

# array([ 493, 870, 1458, ..., 240, 427, 1278])

# Print the most positive words

print("Most positive words: ", end="")

for i in range(5):

print(vocab[inds_descending][i], end=", ")

print("\n")

# Most positive words: favorite, superb, noir, knowing, loved,

# Print most negative words

print("Most negative words: ", end="")

for i in range(5):

print(vocab[inds_ascending][i], end=", ")

print("\n")

# Most negative words: disappointing, waste, worst, boring, lame,

#### Regularization and probabilities

In this exercise, you will observe the effects of changing the regularization strength on the predicted probabilities.

A 2D binary classification dataset is already loaded into the environment as

X

and

y

.

X.shape

(20, 2)

X[:3]

array([[ 1.78862847, 0.43650985],

[ 0.09649747, -1.8634927 ],

[-0.2773882 , -0.35475898]])

y[:3]

array([-1, -1, -1])

# Set the regularization strength

model = LogisticRegression(C=1)

# Fit and plot

model.fit(X,y)

plot_classifier(X,y,model,proba=True)

# Predict probabilities on training points

prob = model.predict_proba(X)

print("Maximum predicted probability", np.max(prob))

C = 1

Maximum predicted probability 0.9761229966765974

C=0.1

Maximum predicted probability 0.8990965659596716

Smaller values of

C

lead to less confident predictions.

That’s because smaller

C

means more regularization, which in turn means smaller coefficients, which means raw model outputs closer to zero.

#### Visualizing easy and difficult examples

In this exercise, you’ll visualize the examples that the logistic regression model is most and least confident about by looking at the largest and smallest predicted probabilities.

The handwritten digits dataset is already loaded into the variables

X

and

y

. The

show_digit

function takes in an integer index and plots the corresponding image, with some extra information displayed above the image.

X.shape

(1797, 64)

X[0]

array([ 0., 0., 5., 13., 9., 1., 0., 0., 0., 0., 13., 15., 10.,

15., 5., 0., 0., 3., 15., 2., 0., 11., 8., 0., 0., 4.,

12., 0., 0., 8., 8., 0., 0., 5., 8., 0., 0., 9., 8.,

0., 0., 4., 11., 0., 1., 12., 7., 0., 0., 2., 14., 5.,

10., 12., 0., 0., 0., 0., 6., 13., 10., 0., 0., 0.])

y[:3]

array([0, 1, 2])

show_digit?

Signature: show_digit(i, lr=None)

Docstring: <no docstring>

File: /tmp/tmp12h5q4tk/<ipython-input-1-5d2049073a74>

Type: function

lr = LogisticRegression()

lr.fit(X,y)

# Get predicted probabilities

proba = lr.predict_proba(X)

# Sort the example indices by their maximum probability

proba_inds = np.argsort(np.max(proba,axis=1))

# Show the most confident (least ambiguous) digit

show_digit(proba_inds[-1], lr)

# Show the least confident (most ambiguous) digit

show_digit(proba_inds[0], lr)

As you can see, the least confident example looks like a weird 4, and the most confident example looks like a very typical 0.

#### Counting the coefficients

If you fit a logistic regression model on a classification problem with 3 classes and 100 features, how many coefficients would you have, including intercepts?

303

100 coefficients + 1 intercept for each binary classifier. (A, B), (B, C), (C, A)

101 * 3 = 303

#### Fitting multi-class logistic regression

In this exercise, you’ll fit the two types of multi-class logistic regression, one-vs-rest and softmax/multinomial, on the handwritten digits data set and compare the results.

# Fit one-vs-rest logistic regression classifier

lr_ovr = LogisticRegression()

lr_ovr.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("OVR training accuracy:", lr_ovr.score(X_train, y_train))

print("OVR test accuracy :", lr_ovr.score(X_test, y_test))

# Fit softmax classifier

lr_mn = LogisticRegression(multi_class='multinomial', solver='lbfgs')

lr_mn.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("Softmax training accuracy:", lr_mn.score(X_train, y_train))

print("Softmax test accuracy :", lr_mn.score(X_test, y_test))

OVR training accuracy: 0.9948032665181886

OVR test accuracy : 0.9644444444444444

Softmax training accuracy: 1.0

Softmax test accuracy : 0.9688888888888889

As you can see, the accuracies of the two methods are fairly similar on this data set.

#### Visualizing multi-class logistic regression

In this exercise we’ll continue with the two types of multi-class logistic regression, but on a toy 2D data set specifically designed to break the one-vs-rest scheme.

The data set is loaded into

X_train

and

y_train

. The two logistic regression objects,

lr_mn

and

lr_ovr

, are already instantiated (with

C=100

), fit, and plotted.

Notice that

lr_ovr

never predicts the dark blue class… yikes! Let’s explore why this happens by plotting one of the binary classifiers that it’s using behind the scenes.

# Print training accuracies

print("Softmax training accuracy:", lr_mn.score(X_train, y_train))

print("One-vs-rest training accuracy:", lr_ovr.score(X_train, y_train))

# Softmax training accuracy: 0.996

# One-vs-rest training accuracy: 0.916

# Create the binary classifier (class 1 vs. rest)

lr_class_1 = LogisticRegression(C=100)

lr_class_1.fit(X_train, y_train==1)

# Plot the binary classifier (class 1 vs. rest)

plot_classifier(X_train, y_train==1, lr_class_1)

As you can see, the binary classifier incorrectly labels almost all points in class 1 (shown as red triangles in the final plot)! Thus, this classifier is not a very effective component of the one-vs-rest classifier.

In general, though, one-vs-rest often works well.

#### One-vs-rest SVM

As motivation for the next and final chapter on support vector machines, we’ll repeat the previous exercise with a non-linear SVM.

Instead of using

LinearSVC

, we’ll now use scikit-learn’s

SVC

object, which is a non-linear “kernel” SVM (much more on what this means in Chapter 4!). Again, your task is to create a plot of the binary classifier for class 1 vs. rest.

# We'll use SVC instead of LinearSVC from now on

from sklearn.svm import SVC

# Create/plot the binary classifier (class 1 vs. rest)

svm_class_1 = SVC()

svm_class_1.fit(X_train, y_train==1)

plot_classifier(X_train, y_train==1, svm_class_1)

The non-linear SVM works fine with one-vs-rest on this dataset because it learns to “surround” class 1.

#### Effect of removing examples

Support vectors are defined as training examples that influence the decision boundary. In this exercise, you’ll observe this behavior by removing non support vectors from the training set.

The wine quality dataset is already loaded into

X

and

y

(first two features only). (Note: we specify

lims

in

plot_classifier()

so that the two plots are forced to use the same axis limits and can be compared directly.)

X.shape

(178, 2)

X[:3]

array([[14.23, 1.71],

[13.2 , 1.78],

[13.16, 2.36]])

set(y)

{0, 1, 2}

# Train a linear SVM

svm = SVC(kernel="linear")

svm.fit(X, y)

plot_classifier(X, y, svm, lims=(11,15,0,6))

# Make a new data set keeping only the support vectors

print("Number of original examples", len(X))

print("Number of support vectors", len(svm.support_))

X_small = X[svm.support_]

y_small = y[svm.support_]

# Train a new SVM using only the support vectors

svm_small = SVC(kernel="linear")

svm_small.fit(X_small, y_small)

plot_classifier(X_small, y_small, svm_small, lims=(11,15,0,6))

By the definition of support vectors, the decision boundaries of the two trained models are the same.

#### GridSearchCV warm-up

Increasing the RBF kernel hyperparameter

gamma

increases training accuracy.

In this exercise we’ll search for the

gamma

that maximizes cross-validation accuracy using scikit-learn’s

GridSearchCV

.

A binary version of the handwritten digits dataset, in which you’re just trying to predict whether or not an image is a “2”, is already loaded into the variables

X

and

y

.

set(y)

{False, True}

X.shape

(898, 64)

X[0]

array([ 0., 1., 10., 15., 11., 1., 0., 0., 0., 3., 8., 8., 11.,

12., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 5., 14., 15., 1., 0., 0., 0.,

0., 11., 15., 2., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 4., 15., 2., 0.,

0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 12., 10., 0., 0., 0., 0., 3., 4.,

10., 16., 1., 0., 0., 0., 13., 16., 15., 10., 0., 0.])

# Instantiate an RBF SVM

svm = SVC()

# Instantiate the GridSearchCV object and run the search

parameters = {'gamma':[0.00001, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1]}

searcher = GridSearchCV(svm, param_grid=parameters)

searcher.fit(X, y)

# Report the best parameters

print("Best CV params", searcher.best_params_)

# Best CV params {'gamma': 0.001}

Larger values of

gamma

are better for training accuracy, but cross-validation helped us find something different (and better!).

#### Jointly tuning gamma and C with GridSearchCV

In the previous exercise the best value of

gamma

was 0.001 using the default value of

C

, which is 1. In this exercise you’ll search for the best combination of

C

and

gamma

using

GridSearchCV

.

As in the previous exercise, the 2-vs-not-2 digits dataset is already loaded, but this time it’s split into the variables

X_train

,

y_train

,

X_test

, and

y_test

.

Even though cross-validation already splits the training set into parts, it’s often a good idea to hold out a separate test set to make sure the cross-validation results are sensible.

# Instantiate an RBF SVM

svm = SVC()

# Instantiate the GridSearchCV object and run the search

parameters = {'C':[0.1, 1, 10], 'gamma':[0.00001, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1]}

searcher = GridSearchCV(svm, param_grid=parameters)

searcher.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Report the best parameters and the corresponding score

print("Best CV params", searcher.best_params_)

print("Best CV accuracy", searcher.best_score_)

# Report the test accuracy using these best parameters

print("Test accuracy of best grid search hypers:", searcher.score(X_test, y_test))

Best CV params {'C': 10, 'gamma': 0.0001}

Best CV accuracy 0.9988864142538976

Test accuracy of best grid search hypers: 0.9988876529477196

Note that the best value of

gamma

, 0.0001, is different from the value of 0.001 that we got in the previous exercise, when we fixed

C=1

. Hyperparameters can affect each other!

#### An advantage of SVMs

Having a limited number of support vectors makes kernel SVMs computationally efficient.

#### An advantage of logistic regression

It naturally outputs meaningful probabilities.

#### Using SGDClassifier

In this final coding exercise, you’ll do a hyperparameter search over the regularization type, regularization strength, and the loss (logistic regression vs. linear SVM) using

SGDClassifier()

.

X_train.shape

(1257, 64)

X_train[0]

array([ 0., 0., 2., 10., 16., 11., 1., 0., 0., 0., 13., 13., 10.,

16., 8., 0., 0., 4., 14., 1., 8., 14., 1., 0., 0., 4.,

15., 12., 15., 8., 0., 0., 0., 0., 6., 7., 14., 5., 0.,

0., 0., 1., 2., 0., 12., 5., 0., 0., 0., 8., 15., 6.,

13., 4., 0., 0., 0., 0., 5., 11., 16., 3., 0., 0.])

set(y_train)

{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9}

# We set random_state=0 for reproducibility

linear_classifier = SGDClassifier(random_state=0)

# Instantiate the GridSearchCV object and run the search

parameters = {'alpha':[0.00001, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1],

'loss':['hinge', 'log'], 'penalty':['l1', 'l2']}

searcher = GridSearchCV(linear_classifier, parameters, cv=10)

searcher.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Report the best parameters and the corresponding score

print("Best CV params", searcher.best_params_)

print("Best CV accuracy", searcher.best_score_)

print("Test accuracy of best grid search hypers:", searcher.score(X_test, y_test))

Best CV params {'alpha': 0.0001, 'loss': 'hinge', 'penalty': 'l1'}

Best CV accuracy 0.94351630867144

Test accuracy of best grid search hypers: 0.9592592592592593

One advantage of

SGDClassifier

is that it’s very fast – this would have taken a lot longer with

LogisticRegression

or

LinearSVC

.

The End.

Thank you for reading.