This is the memo of the 14th course (23 courses in all) of ‘Machine Learning Scientist with Python’ skill track.

You can find the original course HERE .

### Course Description

Not long ago, cutting-edge computer vision algorithms couldn’t differentiate between images of cats and dogs. Today, a skilled data scientist equipped with nothing more than a laptop can classify tens of thousands of objects with greater accuracy than the human eye. In this course, you will use TensorFlow 2.0 to develop, train, and make predictions with the models that have powered major advances in recommendation systems, image classification, and FinTech. You will learn both high-level APIs, which will enable you to design and train deep learning models in 15 lines of code, and low-level APIs, which will allow you to move beyond off-the-shelf routines. You will also learn to accurately predict housing prices, credit card borrower defaults, and images of sign language gestures.

### Table of contents

Throughout this course, we will use

tensorflow

version 2.0 and will exclusively import the submodules needed to complete each exercise. This will usually be done for you, but you will do it in this exercise by importing

constant

from

tensorflow

.

After you have imported

constant

, you will use it to transform a

numpy

array,

credit_numpy

, into a

tensorflow

constant,

credit_constant

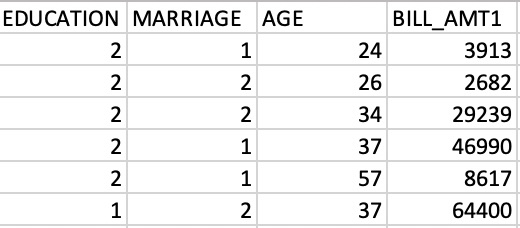

. This array contains feature columns from a dataset on credit card holders and is previewed in the image below. We will return to this dataset in later chapters.

Note that

tensorflow

version 2.0 allows you to use data as either a

numpy

array or a

tensorflow

constant

object. Using a

constant

will ensure that any operations performed with that object are done in

tensorflow

.

# Import constant from TensorFlow

from tensorflow import constant

# Convert the credit_numpy array into a tensorflow constant

credit_constant = constant(credit_numpy)

# Print constant datatype

print('The datatype is:', credit_constant.dtype)

# Print constant shape

print('The shape is:', credit_constant.shape)

The datatype is: <dtype: 'float64'>

The shape is: (30000, 4)

credit_numpy

array([[ 2.0000e+00, 1.0000e+00, 2.4000e+01, 3.9130e+03],

[ 2.0000e+00, 2.0000e+00, 2.6000e+01, 2.6820e+03],

[ 2.0000e+00, 2.0000e+00, 3.4000e+01, 2.9239e+04],

...,

[ 2.0000e+00, 2.0000e+00, 3.7000e+01, 3.5650e+03],

[ 3.0000e+00, 1.0000e+00, 4.1000e+01, -1.6450e+03],

[ 2.0000e+00, 1.0000e+00, 4.6000e+01, 4.7929e+04]])

credit_constant

<tf.Tensor: id=0, shape=(30000, 4), dtype=float64, numpy=

array([[ 2.0000e+00, 1.0000e+00, 2.4000e+01, 3.9130e+03],

[ 2.0000e+00, 2.0000e+00, 2.6000e+01, 2.6820e+03],

[ 2.0000e+00, 2.0000e+00, 3.4000e+01, 2.9239e+04],

...,

[ 2.0000e+00, 2.0000e+00, 3.7000e+01, 3.5650e+03],

[ 3.0000e+00, 1.0000e+00, 4.1000e+01, -1.6450e+03],

[ 2.0000e+00, 1.0000e+00, 4.6000e+01, 4.7929e+04]])>

Excellent! You now understand how constants are used in

tensorflow

. In the following exercise, you’ll practice defining variables.

Unlike a constant, a variable’s value can be modified. This will be quite useful when we want to train a model by updating its parameters. Constants can’t be used for this purpose, so variables are the natural choice.

Let’s try defining and working with a variable. Note that

Variable()

, which is used to create a variable tensor, has been imported from

tensorflow

and is available to use in the exercise.

from tensorflow import Variable

# Define the 1-dimensional variable A1

A1 = Variable([1, 2, 3, 4])

# Print the variable A1

print(A1)

# Convert A1 to a numpy array and assign it to B1

B1 = A1.numpy()

# Print B1

print(B1)

<tf.Variable 'Variable:0' shape=(4,) dtype=int32, numpy=array([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype=int32)>

[1 2 3 4]

Nice work! In our next exercise, we’ll review how to check the properties of a tensor after it is already defined.

Element-wise multiplication in TensorFlow is performed using two tensors with identical shapes. This is because the operation multiplies elements in corresponding positions in the two tensors. An example of an element-wise multiplication, denoted by the ⊙ symbol, is shown below:

In this exercise, you will perform element-wise multiplication, paying careful attention to the shape of the tensors you multiply. Note that

multiply()

,

constant()

, and

ones_like()

have been imported for you.

# Define tensors A1 and A23 as constants

A1 = constant([1, 2, 3, 4])

A23 = constant([[1, 2, 3], [1, 6, 4]])

# Define B1 and B23 to have the correct shape

B1 = ones_like(A1)

B23 = ones_like(A23)

# Perform element-wise multiplication

C1 = multiply(A1,B1)

C23 = multiply(A23,B23)

# Print the tensors C1 and C23

print('C1: {}'.format(C1.numpy()))

print('C23: {}'.format(C23.numpy()))

C1: [1 2 3 4]

C23: [[1 2 3]

[1 6 4]]

ones_like(A1)

<tf.Tensor: id=12, shape=(4,), dtype=int32, numpy=array([1, 1, 1, 1], dtype=int32)>

ones_like(A23)

<tf.Tensor: id=15, shape=(2, 3), dtype=int32, numpy=

array([[1, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 1]], dtype=int32)>

Excellent work! Notice how performing element-wise multiplication with tensors of ones leaves the original tensors unchanged.

In later chapters, you will learn to train linear regression models. This process will yield a vector of parameters that can be multiplied by the input data to generate predictions. In this exercise, you will use input data,

features

, and a target vector,

bill

, which are taken from a credit card dataset we will use later in the course.

The matrix of input data,

features

, contains two columns: education level and age. The target vector,

bill

, is the size of the credit card borrower’s bill.

Since we have not trained the model, you will enter a guess for the values of the parameter vector,

params

. You will then use

matmul()

to perform matrix multiplication of

features

by

params

to generate predictions,

billpred

, which you will compare with

bill

. Note that we have imported

matmul()

and

constant()

.

# Define features, params, and bill as constants

features = constant([[2, 24], [2, 26], [2, 57], [1, 37]])

params = constant([[1000], [150]])

bill = constant([[3913], [2682], [8617], [64400]])

# Compute billpred using features and params

billpred = matmul(features,params)

# Compute and print the error

error = bill - billpred

print(error.numpy())

[[-1687]

[-3218]

[-1933]

[57850]]

billpred

<tf.Tensor: id=15, shape=(4, 1), dtype=int32, numpy=

array([[ 5600],

[ 5900],

[10550],

[ 6550]], dtype=int32)>

Nice job! Understanding matrix multiplication will make things simpler when we start making predictions with linear models.

You’ve been given a matrix,

wealth

. This contains the value of bond and stock wealth for five individuals in thousands of dollars.

The first column corresponds to bonds and the second corresponds to stocks. Each row gives the bond and stock wealth for a single individual. Use

wealth

,

reduce_sum()

, and

.numpy()

to determine which statements are correct about

wealth

.

reduce_sum(wealth,0).numpy()

# array([ 50, 122], dtype=int32)

reduce_sum(wealth,1).numpy()

# array([61, 9, 64, 3, 35], dtype=int32)

reduce_sum(wealth).numpy()

# 172

Combined, the 5 individuals hold $50,000 in bonds.

Excellent work! Understanding how to sum over tensor dimensions will be helpful when preparing datasets and training models.

Later in the course, you will classify images of sign language letters using a neural network. In some cases, the network will take 1-dimensional tensors as inputs, but your data will come in the form of images, which will either be either 2- or 3-dimensional tensors, depending on whether they are grayscale or color images.

The figure below shows grayscale and color images of the sign language letter A. The two images have been imported for you and converted to the numpy arrays

gray_tensor

and

color_tensor

. Reshape these arrays into 1-dimensional vectors using the

reshape

operation, which has been imported for you from

tensorflow

. Note that the shape of

gray_tensor

is 28×28 and the shape of

color_tensor

is 28x28x3.

# Reshape the grayscale image tensor into a vector

gray_vector = reshape(gray_tensor, (28*28, 1))

# Reshape the color image tensor into a vector

color_vector = reshape(color_tensor, (28*28*3, 1))

Excellent work! Notice that there are 3 times as many elements in

color_vector

as there are in

gray_vector

, since

color_tensor

has 3 color channels.

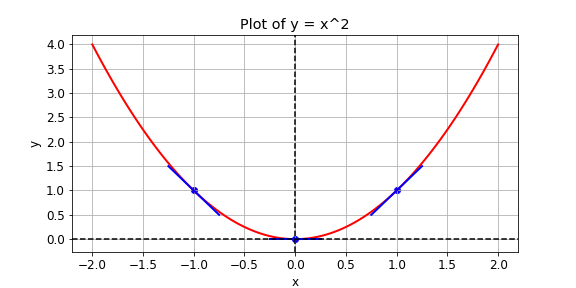

You are given a loss function, y=x2y=x2, which you want to minimize. You can do this by computing the slope using the

GradientTape()

operation at different values of

x

. If the slope is positive, you can decrease the loss by lowering

x

. If it is negative, you can decrease it by increasing

x

. This is how gradient descent works.

In practice, you will use a high level

tensorflow

operation to perform gradient descent automatically. In this exercise, however, you will compute the slope at

x

values of -1, 1, and 0. The following operations are available:

GradientTape()

,

multiply()

, and

Variable()

.

def compute_gradient(x0):

# Define x as a variable with an initial value of x0

x = Variable(x0)

with GradientTape() as tape:

tape.watch(x)

# Define y using the multiply operation

y = multiply(x,x)

# Return the gradient of y with respect to x

return tape.gradient(y, x).numpy()

# Compute and print gradients at x = -1, 1, and 0

print(compute_gradient(-1.0))

# -2.0

print(compute_gradient(1.0))

# 2.0

print(compute_gradient(0.0))

# 0.0

Excellent work! Notice that the slope is positive at

x

= 1, which means that we can lower the loss by reducing

x

. The slope is negative at

x

= -1, which means that we can lower the loss by increasing

x

. The slope at

x

= 0 is 0, which means that we cannot lower the loss by either increasing or decreasing

x

. This is because the loss is minimized at

x

= 0.

You are given a black-and-white image of a letter, which has been encoded as a tensor,

letter

. You want to determine whether the letter is an X or a K. You don’t have a trained neural network, but you do have a simple model,

model

, which can be used to classify

letter

.

The 3×3 tensor,

letter

, and the 1×3 tensor,

model

, are available in the Python shell. You can determine whether

letter

is a K by multiplying

letter

by

model

, summing over the result, and then checking if it is equal to 1. As with more complicated models, such as neural networks,

model

is a collection of weights, arranged in a tensor.

Note that the functions

reshape()

,

matmul()

, and

reduce_sum()

have been imported from

tensorflow

and are available for use.

letter

array([[1., 0., 1.],

[1., 1., 0.],

[1., 0., 1.]], dtype=float32)

# Reshape model from a 1x3 to a 3x1 tensor

model = reshape(model, (3, 1))

# Multiply letter by model

output = matmul(letter, model)

# Sum over output and print prediction using the numpy method

prediction = reduce_sum(output)

print(prediction.numpy())

# 1.0

Excellent work! Your model found that

prediction

=1.0 and correctly classified the letter as a K. In the coming chapters, you will use data to train a model,

model

, and then combine this with matrix multiplication,

matmul(letter, model)

, as we have done here, to make predictions about the classes of objects.

Before you can train a machine learning model, you must first import data. There are several valid ways to do this, but for now, we will use a simple one-liner from

pandas

:

pd.read_csv()

. Recall from the video that the first argument specifies the path or URL. All other arguments are optional.

In this exercise, you will import the King County housing dataset, which we will use to train a linear model later in the chapter.

# Import pandas under the alias pd

import pandas as pd

# Assign the path to a string variable named data_path

data_path = 'kc_house_data.csv'

# Load the dataset as a dataframe named housing

housing = pd.read_csv(data_path)

# Print the price column of housing

print(housing['price'])

Excellent work! Notice that you did not have to specify a delimiter with the

sep

parameter, since the dataset was stored in the default, comma-separated format.

In this exercise, you will both load data and set its type. Note that

housing

is available and

pandas

has been imported as

pd

. You will import

numpy

and

tensorflow

, and define tensors that are usable in

tensorflow

using columns in

housing

with a given data type. Recall that you can select the

price

column, for instance, from

housing

using

housing['price']

.

# Import numpy and tensorflow with their standard aliases

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

# Use a numpy array to define price as a 32-bit float

price = np.array(housing['price'], np.float)

# Define waterfront as a Boolean using cast

waterfront = tf.cast(housing['waterfront'], tf.bool)

# Print price and waterfront

print(price)

print(waterfront)

[221900. 538000. 180000. ... 402101. 400000. 325000.]

tf.Tensor([False False False ... False False False], shape=(21613,), dtype=bool)

Great job! Notice that printing

price

yielded a

numpy

array; whereas printing

waterfront

yielded a

tf.Tensor()

.

In this exercise, you will compute the loss using data from the King County housing dataset. You are given a target,

price

, which is a tensor of house prices, and

predictions

, which is a tensor of predicted house prices. You will evaluate the loss function and print out the value of the loss.

# Import the keras module from tensorflow

from tensorflow import keras

# Compute the mean squared error (mse)

loss = keras.losses.mse(price, predictions)

# Print the mean squared error (mse)

print(loss.numpy())

# 141171604777.12717

# Compute the mean absolute error (mae)

loss = keras.losses.mae(price, predictions)

# Print the mean absolute error (mae)

print(loss.numpy())

# 268827.99302087986

Great work! You may have noticed that the MAE was much smaller than the MSE, even though

price

and

predictions

were the same. This is because the different loss functions penalize deviations of

predictions

from

price

differently. MSE does not like large deviations and punishes them harshly.

In the previous exercise, you defined a

tensorflow

loss function and then evaluated it once for a set of actual and predicted values. In this exercise, you will compute the loss within another function called

loss_function()

, which first generates predicted values from the data and variables. The purpose of this is to construct a function of the trainable model variables that returns the loss. You can then repeatedly evaluate this function for different variable values until you find the minimum. In practice, you will pass this function to an optimizer in

tensorflow

. Note that

features

and

targets

have been defined and are available. Additionally,

Variable

,

float32

, and

keras

are available.

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow import Variable

from tensorflow import keras

# Initialize a variable named scalar

scalar = Variable(1.0, tf.float32)

# Define the model

def model(scalar, features = features):

return scalar * features

# Define a loss function

def loss_function(scalar, features = features, targets = targets):

# Compute the predicted values

predictions = model(scalar, features)

# Return the mean absolute error loss

return keras.losses.mae(targets, predictions)

# Evaluate the loss function and print the loss

print(loss_function(scalar).numpy())

# 3.0

Great work! As you will see in the following lessons, this exercise was the equivalent of evaluating the loss function for a linear regression where the intercept is 0.

A univariate linear regression identifies the relationship between a single feature and the target tensor. In this exercise, we will use a property’s lot size and price. Just as we discussed in the video, we will take the natural logarithms of both tensors, which are available as

price_log

and

size_log

.

In this exercise, you will define the model and the loss function. You will then evaluate the loss function for two different values of

intercept

and

slope

. Remember that the predicted values are given by

intercept + features*slope

. Additionally, note that

keras.losses.mse()

is available for you. Furthermore,

slope

and

intercept

have been defined as variables.

# Define a linear regression model

def linear_regression(intercept, slope, features = size_log):

return intercept + slope*features

# Set loss_function() to take the variables as arguments

def loss_function(intercept, slope, features = size_log, targets = price_log):

# Set the predicted values

predictions = linear_regression(intercept, slope, features)

# Return the mean squared error loss

return keras.losses.mse(targets, predictions)

# Compute the loss for different slope and intercept values

print(loss_function(0.1, 0.1).numpy())

print(loss_function(0.1, 0.5).numpy())

# 145.44652

# 71.866

Great work! In the next exercise, you will actually run the regression and train

intercept

and

slope

.

In this exercise, we will pick up where the previous exercise ended. The intercept and slope,

intercept

and

slope

, have been defined and initialized. Additionally, a function has been defined,

loss_function(intercept, slope)

, which computes the loss using the data and model variables.

You will now define an optimization operation as

opt

. You will then train a univariate linear model by minimizing the loss to find the optimal values of

intercept

and

slope

. Note that the

opt

operation will try to move closer to the optimum with each step, but will require many steps to find it. Thus, you must repeatedly execute the operation.

# Initialize an adam optimizer

opt = keras.optimizers.Adam(0.5)

for j in range(100):

# Apply minimize, pass the loss function, and supply the variables

opt.minimize(lambda: loss_function(intercept, slope), var_list=[intercept, slope])

# Print every 10th value of the loss

if j % 10 == 0:

print(loss_function(intercept, slope).numpy())

# Plot data and regression line

plot_results(intercept, slope)

9.669481

11.726705

1.1193314

1.6605749

0.7982892

0.8017315

0.6106562

0.59997994

0.5811015

0.5576157

Excellent! Notice that we printed

loss_function(intercept, slope)

every 10th execution for 100 executions. Each time, the loss got closer to the minimum as the optimizer moved the

slope

and

intercept

parameters closer to their optimal values.

In most cases, performing a univariate linear regression will not yield a model that is useful for making accurate predictions. In this exercise, you will perform a multiple regression, which uses more than one feature.

You will use

price_log

as your target and

size_log

and

bedrooms

as your features. Each of these tensors has been defined and is available. You will also switch from using the the mean squared error loss to the mean absolute error loss:

keras.losses.mae()

. Finally, the predicted values are computed as follows:

params[0] + feature1*params[1] + feature2*params[2]

. Note that we’ve defined a vector of parameters,

params

, as a variable, rather than using three variables. Here,

params[0]

is the intercept and

params[1]

and

params[2]

are the slopes.

# Define the linear regression model

def linear_regression(params, feature1 = size_log, feature2 = bedrooms):

return params[0] + feature1*params[1] + feature2*params[2]

# Define the loss function

def loss_function(params, targets = price_log, feature1 = size_log, feature2 = bedrooms):

# Set the predicted values

predictions = linear_regression(params, feature1, feature2)

# Use the mean absolute error loss

return keras.losses.mae(targets, predictions)

# Define the optimize operation

opt = keras.optimizers.Adam()

# Perform minimization and print trainable variables

for j in range(10):

opt.minimize(lambda: loss_function(params), var_list=[params])

print_results(params)

loss: 12.418, intercept: 0.101, slope_1: 0.051, slope_2: 0.021

loss: 12.404, intercept: 0.102, slope_1: 0.052, slope_2: 0.022

loss: 12.391, intercept: 0.103, slope_1: 0.053, slope_2: 0.023

loss: 12.377, intercept: 0.104, slope_1: 0.054, slope_2: 0.024

loss: 12.364, intercept: 0.105, slope_1: 0.055, slope_2: 0.025

loss: 12.351, intercept: 0.106, slope_1: 0.056, slope_2: 0.026

loss: 12.337, intercept: 0.107, slope_1: 0.057, slope_2: 0.027

loss: 12.324, intercept: 0.108, slope_1: 0.058, slope_2: 0.028

loss: 12.311, intercept: 0.109, slope_1: 0.059, slope_2: 0.029

loss: 12.297, intercept: 0.110, slope_1: 0.060, slope_2: 0.030

Great job! Note that

params[2]

tells us how much the price will increase in percentage terms if we add one more bedroom. You could train

params[2]

and the other model parameters by increasing the number of times we iterate over

opt

.

Before we can train a linear model in batches, we must first define variables, a loss function, and an optimization operation. In this exercise, we will prepare to train a model that will predict

price_batch

, a batch of house prices, using

size_batch

, a batch of lot sizes in square feet. In contrast to the previous lesson, we will do this by loading batches of data using

pandas

, converting it to

numpy

arrays, and then using it to minimize the loss function in steps.

Variable()

,

keras()

, and

float32

have been imported for you. Note that you should not set default argument values for either the model or loss function, since we will generate the data in batches during the training process.

# Define the intercept and slope

intercept = Variable(10.0, float32)

slope = Variable(0.5, float32)

# Define the model

def linear_regression(intercept, slope, features):

# Define the predicted values

return intercept + slope*features

# Define the loss function

def loss_function(intercept, slope, targets, features):

# Define the predicted values

predictions = linear_regression(intercept, slope, features)

# Define the MSE loss

return keras.losses.mse(targets, predictions)

Excellent work! Notice that we did not use default argument values for the input data,

features

and

targets

. This is because the input data has not been defined in advance. Instead, with batch training, we will load it during the training process.

In this exercise, we will train a linear regression model in batches, starting where we left off in the previous exercise. We will do this by stepping through the dataset in batches and updating the model’s variables,

intercept

and

slope

, after each step. This approach will allow us to train with datasets that are otherwise too large to hold in memory.

Note that the loss function,

loss_function(intercept, slope, targets, features)

, has been defined for you. Additionally,

keras

has been imported for you and

numpy

is available as

np

. The trainable variables should be entered into

var_list

in the order in which they appear as loss function arguments.

# Initialize adam optimizer

opt = keras.optimizers.Adam()

# Load data in batches

for batch in pd.read_csv('kc_house_data.csv', chunksize=100):

size_batch = np.array(batch['sqft_lot'], np.float32)

# Extract the price values for the current batch

price_batch = np.array(batch['price'], np.float32)

# Complete the loss, fill in the variable list, and minimize

opt.minimize(lambda: loss_function(intercept, slope, price_batch, size_batch), var_list=[intercept, slope])

# Print trained parameters

print(intercept.numpy(), slope.numpy())

# 10.217888 0.7016

Great work! Batch training will be very useful when you train neural networks, which we will do next.

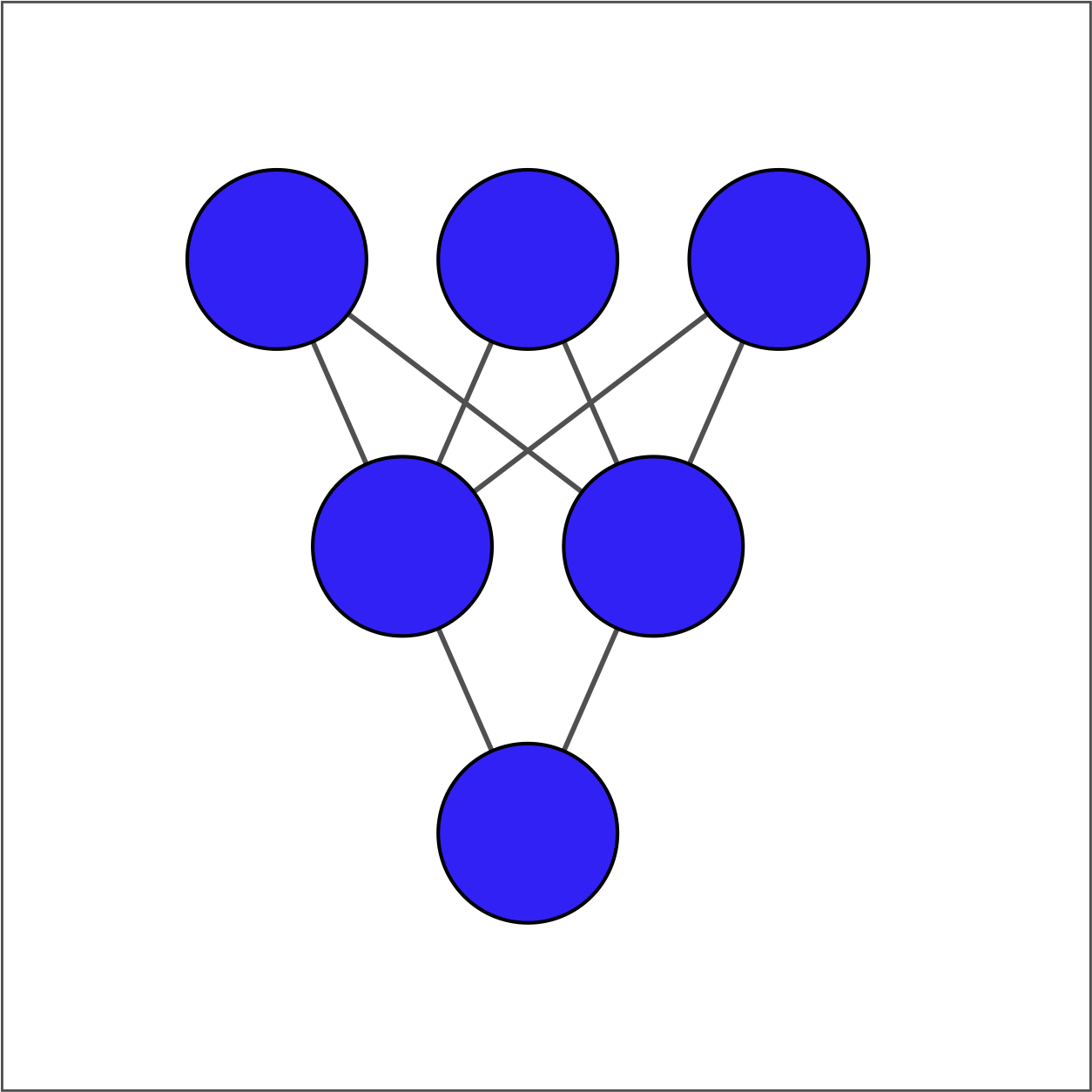

There are two ways to define a dense layer in

tensorflow

. The first involves the use of low-level, linear algebraic operations. The second makes use of high-level

keras

operations. In this exercise, we will use the first method to construct the network shown in the image below.

The input layer contains 3 features — education, marital status, and age — which are available as

borrower_features

. The hidden layer contains 2 nodes and the output layer contains a single node.

For each layer, you will take the previous layer as an input, initialize a set of weights, compute the product of the inputs and weights, and then apply an activation function. Note that

Variable()

,

ones()

,

matmul()

, and

keras()

have been imported from

tensorflow

.

# Initialize bias1

bias1 = Variable(1.0)

# Initialize weights1 as 3x2 variable of ones

weights1 = Variable(ones((3, 2)))

# Perform matrix multiplication of borrower_features and weights1

product1 = matmul(borrower_features,weights1)

# Apply sigmoid activation function to product1 + bias1

dense1 = keras.activations.sigmoid(product1 + bias1)

# Print shape of dense1

print("\n dense1's output shape: {}".format(dense1.shape))

# dense1's output shape: (1, 2)

# From previous step

bias1 = Variable(1.0)

weights1 = Variable(ones((3, 2)))

product1 = matmul(borrower_features, weights1)

dense1 = keras.activations.sigmoid(product1 + bias1)

# Initialize bias2 and weights2

bias2 = Variable(1.0)

weights2 = Variable(ones((2, 1)))

# Perform matrix multiplication of dense1 and weights2

product2 = matmul(dense1, weights2)

# Apply activation to product2 + bias2 and print the prediction

prediction = keras.activations.sigmoid(product2 + bias2)

print('\n prediction: {}'.format(prediction.numpy()[0,0]))

print('\n actual: 1')

prediction: 0.9525741338729858

actual: 1

Excellent work! Our model produces predicted values in the interval between 0 and 1. For the example we considered, the actual value was 1 and the predicted value was a probability between 0 and 1. This, of course, is not meaningful, since we have not yet trained our model’s parameters.

In this exercise, we’ll build further intuition for the low-level approach by constructing the first dense hidden layer for the case where we have multiple examples. We’ll assume the model is trained and the first layer weights,

weights1

, and bias,

bias1

, are available. We’ll then perform matrix multiplication of the

borrower_features

tensor by the

weights1

variable. Recall that the

borrower_features

tensor includes education, marital status, and age. Finally, we’ll apply the sigmoid function to the elements of

products1 + bias1

, yielding

dense1

.

Note that

matmul()

and

keras()

have been imported from

tensorflow

.

# Compute the product of borrower_features and weights1

products1 = matmul(borrower_features,weights1)

# Apply a sigmoid activation function to products1 + bias1

dense1 = keras.activations.sigmoid(products1+bias1)

# Print the shapes of borrower_features, weights1, bias1, and dense1

print('\n shape of borrower_features: ', borrower_features.shape)

# shape of borrower_features: (5, 3)

print('\n shape of weights1: ', weights1.shape)

# shape of weights1: (3, 2)

print('\n shape of bias1: ', bias1.shape)

# shape of bias1: (1,)

print('\n shape of dense1: ', dense1.shape)

# shape of dense1: (5, 2)

Good job! Note that our input data,

borrower_features

, is 5×3 because it consists of 5 examples for 3 features. The shape of

weights1

is 3×2, as it was in the previous exercise, since it does not depend on the number of examples. Additionally,

bias1

is a scalar. Finally,

dense1

is 5×2, which means that we can multiply it by the following set of weights,

weights2

, which we defined to be 2×1 in the previous exercise.

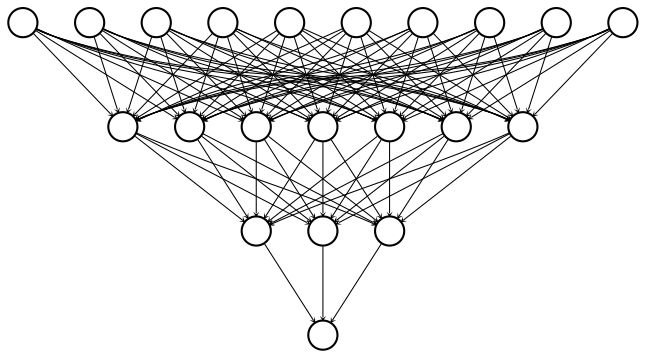

We’ve now seen how to define dense layers in

tensorflow

using linear algebra. In this exercise, we’ll skip the linear algebra and let

keras

work out the details. This will allow us to construct the network below, which has 2 hidden layers and 10 features, using less code than we needed for the network with 1 hidden layer and 3 features.

To construct this network, we’ll need to define three dense layers, each of which takes the previous layer as an input, multiplies it by weights, and applies an activation function. Note that input data has been defined and is available as a 100×10 tensor:

borrower_features

. Additionally, the

keras.layers

module is available.

# Define the first dense layer

dense1 = keras.layers.Dense(7, activation='sigmoid')(borrower_features)

# Define a dense layer with 3 output nodes

dense2 = keras.layers.Dense(3, activation='sigmoid')(dense1)

# Define a dense layer with 1 output node

predictions = keras.layers.Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')(dense2)

# Print the shapes of dense1, dense2, and predictions

print('\n shape of dense1: ', dense1.shape)

# shape of dense1: (100, 7)

print('\n shape of dense2: ', dense2.shape)

# shape of dense2: (100, 3)

print('\n shape of predictions: ', predictions.shape)

# shape of predictions: (100, 1)

Great work! With just 8 lines of code, you were able to define 2 dense hidden layers and an output layer. This is the advantage of using high-level operations in

tensorflow

. Note that each layer has 100 rows because the input data contains 100 examples.

In this exercise, you will again make use of credit card data. The target variable,

default

, indicates whether a credit card holder defaults on her payment in the following period. Since there are only two options–default or not–this is a binary classification problem. While the dataset has many features, you will focus on just three: the size of the three latest credit card bills. Finally, you will compute predictions from your untrained network,

outputs

, and compare those the target variable,

default

.

The tensor of features has been loaded and is available as

bill_amounts

. Additionally, the

constant()

,

float32

, and

keras.layers.Dense()

operations are available.

# Construct input layer from features

inputs = constant(bill_amounts)

# Define first dense layer

dense1 = keras.layers.Dense(3, activation='relu')(inputs)

# Define second dense layer

dense2 = keras.layers.Dense(2, activation='relu')(dense1)

# Define output layer

outputs = keras.layers.Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')(dense2)

# Print error for first five examples

error = default[:5] - outputs.numpy()[:5]

print(error)

[[ 0.0000000e+00]

[ 3.4570694e-05]

[-1.0000000e+00]

[-1.0000000e+00]

[-1.0000000e+00]]

Excellent work! If you run the code several times, you’ll notice that the errors change each time. This is because you’re using an untrained model with randomly initialized parameters. Furthermore, the errors fall on the interval between -1 and 1 because

default

is a binary variable that takes on values of 0 and 1 and

outputs

is a probability between 0 and 1.

In this exercise, we expand beyond binary classification to cover multiclass problems. A multiclass problem has targets that can take on three or more values. In the credit card dataset, the education variable can take on 6 different values, each corresponding to a different level of education. We will use that as our target in this exercise and will also expand the feature set from 3 to 10 columns.

As in the previous problem, you will define an input layer, dense layers, and an output layer. You will also print the untrained model’s predictions, which are probabilities assigned to the classes. The tensor of features has been loaded and is available as

borrower_features

. Additionally, the

constant()

,

float32

, and

keras.layers.Dense()

operations are available.

import tensorflow as tf

# Construct input layer from borrower features

inputs = constant(borrower_features,tf.float32)

# Define first dense layer

dense1 = keras.layers.Dense(10, activation='sigmoid')(inputs)

# Define second dense layer

dense2 = keras.layers.Dense(8, activation='relu')(dense1)

# Define output layer

outputs = keras.layers.Dense(6, activation='softmax')(dense2)

# Print first five predictions

print(outputs.numpy()[:5])

[[0.17133032 0.16293828 0.14702542 0.17789574 0.16075517 0.18005505]

[0.15597914 0.17065835 0.1275746 0.2044413 0.16524555 0.17610106]

[0.15597914 0.17065835 0.1275746 0.2044413 0.16524555 0.17610106]

[0.17133032 0.16293828 0.14702542 0.17789574 0.16075517 0.18005505]

[0.07605464 0.17264706 0.15399623 0.2247733 0.1516134 0.22091544]]

Great work! Notice that each row of

outputs

sums to one. This is because a row contains the predicted class probabilities for one example. As with the previous exercise, our predictions are not yet informative, since we are using an untrained model with randomly initialized parameters. This is why the model tends to assign similar probabilities to each class.

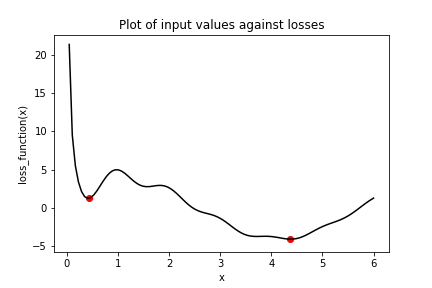

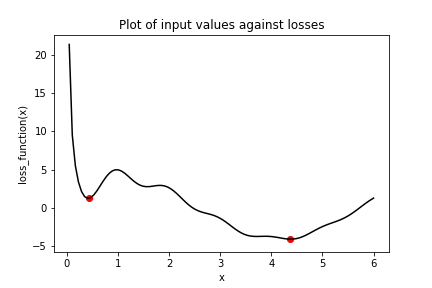

Consider the plot of the following loss function,

loss_function()

, which contains a global minimum, marked by the dot on the right, and several local minima, including the one marked by the dot on the left.

In this exercise, you will try to find the global minimum of

loss_function()

using

keras.optimizers.SGD()

. You will do this twice, each time with a different initial value of the input to

loss_function()

. First, you will use

x_1

, which is a variable with an initial value of 6.0. Second, you will use

x_2

, which is a variable with an initial value of 0.3. Note that

loss_function()

has been defined and is available.

# Initialize x_1 and x_2

x_1 = Variable(6.0,float32)

x_2 = Variable(0.3,float32)

# Define the optimization operation

opt = keras.optimizers.SGD(learning_rate=0.01)

for j in range(100):

# Perform minimization using the loss function and x_1

opt.minimize(lambda: loss_function(x_1), var_list=[x_1])

# Perform minimization using the loss function and x_2

opt.minimize(lambda: loss_function(x_2), var_list=[x_2])

# Print x_1 and x_2 as numpy arrays

print(x_1.numpy(), x_2.numpy())

# 4.3801394 0.42052683

Great work! Notice that we used the same optimizer and loss function, but two different initial values. When we started at 6.0 with

x_1

, we found the global minimum at 4.38, marked by the dot on the right. When we started at 0.3, we stopped around 0.42 with

x_2

, the local minimum marked by a dot on the far left.

The previous problem showed how easy it is to get stuck in local minima. We had a simple optimization problem in one variable and gradient descent still failed to deliver the global minimum when we had to travel through local minima first. One way to avoid this problem is to use momentum, which allows the optimizer to break through local minima. We will again use the loss function from the previous problem, which has been defined and is available for you as

loss_function()

.

Several optimizers in

tensorflow

have a momentum parameter, including

SGD

and

RMSprop

. You will make use of

RMSprop

in this exercise. Note that

x_1

and

x_2

have been initialized to the same value this time. Furthermore,

keras.optimizers.RMSprop()

has also been imported for you from

tensorflow

.

# Initialize x_1 and x_2

x_1 = Variable(0.05,float32)

x_2 = Variable(0.05,float32)

# Define the optimization operation for opt_1 and opt_2

opt_1 = keras.optimizers.RMSprop(learning_rate=0.01, momentum=0.99)

opt_2 = keras.optimizers.RMSprop(learning_rate=0.01, momentum=0.00)

for j in range(100):

opt_1.minimize(lambda: loss_function(x_1), var_list=[x_1])

# Define the minimization operation for opt_2

opt_2.minimize(lambda: loss_function(x_2), var_list=[x_2])

# Print x_1 and x_2 as numpy arrays

print(x_1.numpy(), x_2.numpy())

# 4.3150263 0.4205261

Good work! Recall that the global minimum is approximately 4.38. Notice that

opt_1

built momentum, bringing

x_1

closer to the global minimum. To the contrary,

opt_2

, which had a

momentum

parameter of 0.0, got stuck in the local minimum on the left.

A good initialization can reduce the amount of time needed to find the global minimum. In this exercise, we will initialize weights and biases for a neural network that will be used to predict credit card default decisions. To build intuition, we will use the low-level, linear algebraic approach, rather than making use of convenience functions and high-level

keras

operations. We will also expand the set of input features from 3 to 23. Several operations have been imported from

tensorflow

:

Variable()

,

random()

, and

ones()

.

# Define the layer 1 weights

w1 = Variable(random.normal([23, 7]))

# Initialize the layer 1 bias

b1 = Variable(ones([7]))

# Define the layer 2 weights

w2 = Variable(random.normal([7, 1]))

# Define the layer 2 bias

b2 = Variable((0))

Variable(random.normal([7, 1]))

<tf.Variable 'Variable:0' shape=(7, 1) dtype=float32, numpy=

array([[ 0.654808 ],

[ 0.05108023],

[-0.4015795 ],

[ 0.17105988],

[-0.71988714],

[ 1.8440487 ],

[-0.0194056 ]], dtype=float32)>

Excellent work! In the next exercise, you will start where we’ve ended and will finish constructing the neural network.

In this exercise, you will train a neural network to predict whether a credit card holder will default. The features and targets you will use to train your network are available in the Python shell as

borrower_features

and

default

. You defined the weights and biases in the previous exercise.

Note that the

predictions

layer is defined as σ(layer1∗w2+b2)σ(layer1∗w2+b2), where σσ is the sigmoid activation,

layer1

is a tensor of nodes for the first hidden dense layer,

w2

is a tensor of weights, and

b2

is the bias tensor.

The trainable variables are

w1

,

b1

,

w2

, and

b2

. Additionally, the following operations have been imported for you:

keras.activations.relu()

and

keras.layers.Dropout()

.

# Define the model

def model(w1, b1, w2, b2, features = borrower_features):

# Apply relu activation functions to layer 1

layer1 = keras.activations.relu(matmul(features, w1) + b1)

# Apply dropout

dropout = keras.layers.Dropout(0.25)(layer1)

return keras.activations.sigmoid(matmul(dropout, w2) + b2)

# Define the loss function

def loss_function(w1, b1, w2, b2, features = borrower_features, targets = default):

predictions = model(w1, b1, w2, b2)

# Pass targets and predictions to the cross entropy loss

return keras.losses.binary_crossentropy(targets, predictions)

Nice work! One of the benefits of using

tensorflow

is that you have the option to customize models down to the linear algebraic-level, as we’ve shown in the last two exercises. If you print

w1

, you can see that the objects we’re working with are simply tensors.

In the previous exercise, you defined a model,

model(w1, b1, w2, b2, features)

, and a loss function,

loss_function(w1, b1, w2, b2, features, targets)

, both of which are available to you in this exercise. You will now train the model and then evaluate its performance by predicting default outcomes in a test set, which consists of

test_features

and

test_targets

and is available to you. The trainable variables are

w1

,

b1

,

w2

, and

b2

. Additionally, the following operations have been imported for you:

keras.activations.relu()

and

keras.layers.Dropout()

.

# Train the model

for j in range(100):

# Complete the optimizer

opt.minimize(lambda: loss_function(w1, b1, w2, b2),

var_list=[w1, b1, w2, b2])

# Make predictions with model

model_predictions = model(w1, b1, w2, b2, test_features)

# Construct the confusion matrix

confusion_matrix(test_targets, model_predictions)

Nice work! The diagram shown is called a “confusion matrix.” The diagonal elements show the number of correct predictions. The off-diagonal elements show the number of incorrect predictions. We can see that the model performs reasonably-well, but does so by overpredicting non-default. This suggests that we may need to train longer, tune the model’s hyperparameters, or change the model’s architecture.

In chapter 3, we used components of the

keras

API in

tensorflow

to define a neural network, but we stopped short of using its full capabilities to streamline model definition and training. In this exercise, you will use the

keras

sequential model API to define a neural network that can be used to classify images of sign language letters. You will also use the

.summary()

method to print the model’s architecture, including the shape and number of parameters associated with each layer.

Note that the images were reshaped from (28, 28) to (784,), so that they could be used as inputs to a dense layer. Additionally, note that

keras

has been imported from

tensorflow

for you.

# Define a Keras sequential model

model = keras.Sequential()

# Define the first dense layer

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(16, activation='relu', input_shape=(784,)))

# Define the second dense layer

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(8, activation='relu'))

# Define the output layer

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(4, activation='softmax'))

# Print the model architecture

print(model.summary())

Model: "sequential"

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

dense (Dense) (None, 16) 12560

_________________________________________________________________

dense_1 (Dense) (None, 8) 136

_________________________________________________________________

dense_2 (Dense) (None, 4) 36

=================================================================

Total params: 12,732

Trainable params: 12,732

Non-trainable params: 0

_________________________________________________________________

None

Excellent work! Notice that we’ve defined a model, but we haven’t compiled it. The compilation step in

keras

allows us to set the optimizer, loss function, and other useful training parameters in a single line of code. Furthermore, the

.summary()

method allows us to view the model’s architecture.

In this exercise, you will work towards classifying letters from the Sign Language MNIST dataset; however, you will adopt a different network architecture than what you used in the previous exercise. There will be fewer layers, but more nodes. You will also apply dropout to prevent overfitting. Finally, you will compile the model to use the

adam

optimizer and the

categorical_crossentropy

loss. You will also use a method in

keras

to summarize your model’s architecture. Note that

keras

has been imported from

tensorflow

for you and a sequential

keras

model has been defined as

model

.

# Define the first dense layer

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(16, activation='sigmoid', input_shape=(784,)))

# Apply dropout to the first layer's output

model.add(keras.layers.Dropout(0.25))

# Define the output layer

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(4, activation='softmax'))

# Compile the model

model.compile('adam', loss='categorical_crossentropy')

# Print a model summary

print(model.summary())

Model: "sequential"

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

dense (Dense) (None, 16) 12560

_________________________________________________________________

dense_1 (Dense) (None, 16) 272

_________________________________________________________________

dropout (Dropout) (None, 16) 0

_________________________________________________________________

dense_2 (Dense) (None, 4) 68

=================================================================

Total params: 12,900

Trainable params: 12,900

Non-trainable params: 0

_________________________________________________________________

None

Great work! You’ve now defined and compiled a neural network using the

keras

sequential model. Notice that printing the

.summary()

method shows the layer type, output shape, and number of parameters of each layer.

In some cases, the sequential API will not be sufficiently flexible to accommodate your desired model architecture and you will need to use the functional API instead. If, for instance, you want to train two models with different architectures jointly, you will need to use the functional API to do this. In this exercise, we will see how to do this. We will also use the

.summary()

method to examine the joint model’s architecture.

Note that

keras

has been imported from

tensorflow

for you. Additionally, the input layers of the first and second models have been defined as

m1_inputs

and

m2_inputs

, respectively. Note that the two models have the same architecture, but one of them uses a

sigmoid

activation in the first layer and the other uses a

relu

.

# For model 1, pass the input layer to layer 1 and layer 1 to layer 2

m1_layer1 = keras.layers.Dense(12, activation='sigmoid')(m1_inputs)

m1_layer2 = keras.layers.Dense(4, activation='softmax')(m1_layer1)

# For model 2, pass the input layer to layer 1 and layer 1 to layer 2

m2_layer1 = keras.layers.Dense(12, activation='relu')(m2_inputs)

m2_layer2 = keras.layers.Dense(4, activation='softmax')(m2_layer1)

# Merge model outputs and define a functional model

merged = keras.layers.add([m1_layer2, m2_layer2])

model = keras.Model(inputs=[m1_inputs, m2_inputs], outputs=merged)

# Print a model summary

print(model.summary())

Model: "model"

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param # Connected to

==================================================================================================

input_1 (InputLayer) [(None, 784)] 0

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

input_2 (InputLayer) [(None, 784)] 0

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

dense (Dense) (None, 12) 9420 input_1[0][0]

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

dense_2 (Dense) (None, 12) 9420 input_2[0][0]

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

dense_1 (Dense) (None, 4) 52 dense[0][0]

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

dense_3 (Dense) (None, 4) 52 dense_2[0][0]

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

add (Add) (None, 4) 0 dense_1[0][0]

dense_3[0][0]

==================================================================================================

Total params: 18,944

Trainable params: 18,944

Non-trainable params: 0

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

None

Nice work! Notice that the

.summary()

method yields a new column:

connected to

. This column tells you how layers connect to each other within the network. We can see that

dense_2

, for instance, is connected to the

input_2

layer. We can also see that the

add

layer, which merged the two models, connected to both

dense_1

and

dense_3

.

In this exercise, we return to our sign language letter classification problem. We have 2000 images of four letters–A, B, C, and D–and we want to classify them with a high level of accuracy. We will complete all parts of the problem, including the model definition, compilation, and training.

Note that

keras

has been imported from

tensorflow

for you. Additionally, the features are available as

sign_language_features

and the targets are available as

sign_language_labels

.

# Define a sequential model

model = keras.Sequential()

# Define a hidden layer

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(16, activation='relu', input_shape=(784,)))

# Define the output layer

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(4, activation='softmax'))

# Compile the model

model.compile('SGD', loss='categorical_crossentropy')

# Complete the fitting operation

model.fit(sign_language_features, sign_language_labels, epochs=5)

Train on 1999 samples

Epoch 1/5

32/1999 [..............................] - ETA: 29s - loss: 1.6657

...

Epoch 5/5

...

1999/1999 [==============================] - 0s 92us/sample - loss: 0.4493

Great work! You probably noticed that your only measure of performance improvement was the value of the loss function in the training sample, which is not particularly informative. You will improve on this in the next exercise.

We trained a model to predict sign language letters in the previous exercise, but it is unclear how successful we were in doing so. In this exercise, we will try to improve upon the interpretability of our results. Since we did not use a validation split, we only observed performance improvements within the training set; however, it is unclear how much of that was due to overfitting. Furthermore, since we did not supply a metric, we only saw decreases in the loss function, which do not have any clear interpretation.

Note that

keras

has been imported for you from

tensorflow

.

# Define sequential model

model = keras.Sequential()

# Define the first layer

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(32, activation='sigmoid', input_shape=(784,)))

# Add activation function to classifier

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(4, activation='softmax'))

# Set the optimizer, loss function, and metrics

model.compile(optimizer='RMSprop', loss='categorical_crossentropy', metrics=['accuracy'])

# Add the number of epochs and the validation split

model.fit(sign_language_features, sign_language_labels, epochs=10, validation_split=0.1)

Train on 1799 samples, validate on 200 samples

Epoch 1/10

32/1799 [..............................] - ETA: 43s - loss: 1.6457 - accuracy: 0.2500

...

Epoch 10/10

...

1799/1799 [==============================] - 0s 119us/sample - loss: 0.1381 - accuracy: 0.9772 - val_loss: 0.1356 - val_accuracy: 0.9700

Nice work! With the

keras

API, you only needed 14 lines of code to define, compile, train, and validate a model. You may have noticed that your model performed quite well. In just 10 epochs, we achieved a classification accuracy of around 98% in the validation sample!

In this exercise, we’ll work with a small subset of the examples from the original sign language letters dataset. A small sample, coupled with a heavily-parameterized model, will generally lead to overfitting. This means that your model will simply memorize the class of each example, rather than identifying features that generalize to many examples.

You will detect overfitting by checking whether the validation sample loss is substantially higher than the training sample loss and whether it increases with further training. With a small sample and a high learning rate, the model will struggle to converge on an optimum. You will set a low learning rate for the optimizer, which will make it easier to identify overfitting.

Note that

keras

has been imported from

tensorflow

.

# Define sequential model

model = keras.Sequential()

# Define the first layer

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(1024, activation='relu', input_shape=(784,)))

# Add activation function to classifier

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(4, activation='softmax'))

# Finish the model compilation

model.compile(optimizer=keras.optimizers.Adam(lr=0.01),

loss='categorical_crossentropy', metrics=['accuracy'])

# Complete the model fit operation

model.fit(sign_language_features, sign_language_labels, epochs=200, validation_split=0.5)

Train on 25 samples, validate on 25 samples

Epoch 1/200

25/25 [==============================] - 1s 37ms/sample - loss: 1.5469 - accuracy: 0.2000 - val_loss: 48.8668 - val_accuracy: 0.2400

...

Epoch 200/200

25/25 [==============================] - 0s 669us/sample - loss: 0.0068 - accuracy: 1.0000 - val_loss: 0.5236 - val_accuracy: 0.8400

Excellent work! You may have noticed that the validation loss,

val_loss

, was substantially higher than the training loss,

loss

. Furthermore, if

val_loss

started to increase before the training process was terminated, then we may have overfitted. When this happens, you will want to try decreasing the number of epochs.

Two models have been trained and are available:

large_model

, which has many parameters; and

small_model

, which has fewer parameters. Both models have been trained using

train_features

and

train_labels

, which are available to you. A separate test set, which consists of

test_features

and

test_labels

, is also available.

Your goal is to evaluate relative model performance and also determine whether either model exhibits signs of overfitting. You will do this by evaluating

large_model

and

small_model

on both the train and test sets. For each model, you can do this by applying the

.evaluate(x, y)

method to compute the loss for features

x

and labels

y

. You will then compare the four losses generated.

# Evaluate the small model using the train data

small_train = small_model.evaluate(train_features, train_labels)

# Evaluate the small model using the test data

small_test = small_model.evaluate(test_features, test_labels)

# Evaluate the large model using the train data

large_train = large_model.evaluate(train_features, train_labels)

# Evaluate the large model using the test data

large_test = large_model.evaluate(test_features, test_labels)

# Print losses

print('\n Small - Train: {}, Test: {}'.format(small_train, small_test))

print('Large - Train: {}, Test: {}'.format(large_train, large_test))

Small - Train: 0.7137059640884399, Test: 0.8472499084472657

Large - Train: 0.036491363495588305, Test: 0.1792870020866394

Great job! Notice that the gap between the test and train set losses is substantially higher for

large_model

, suggesting that overfitting may be an issue. Furthermore, both test and train set performance is better for

large_model

. This suggests that we may want to use

large_model

, but reduce the number of training epochs.

For this exercise, we’ll return to the King County housing transaction dataset from chapter 2. We will again develop and train a machine learning model to predict house prices; however, this time, we’ll do it using the

estimator

API.

Rather than completing everything in one step, we’ll break this procedure down into parts. We’ll begin by defining the feature columns and loading the data. In the next exercise, we’ll define and train a premade

estimator

. Note that

feature_column

has been imported for you from

tensorflow

. Additionally,

numpy

has been imported as

np

, and the Kings County housing dataset is available as a

pandas

DataFrame

:

housing

.

housing.columns

Index(['id', 'date', 'price', 'bedrooms', 'bathrooms', 'sqft_living', 'sqft_lot', 'floors', 'waterfront', 'view', 'condition', 'grade', 'sqft_above', 'sqft_basement', 'yr_built', 'yr_renovated',

'zipcode', 'lat', 'long', 'sqft_living15', 'sqft_lot15'],

dtype='object')

housing.shape

(21613, 21)

# Define feature columns for bedrooms and bathrooms

bedrooms = feature_column.numeric_column("bedrooms")

bathrooms = feature_column.numeric_column("bathrooms")

# Define the list of feature columns

feature_list = [bedrooms, bathrooms]

def input_fn():

# Define the labels

labels = np.array(housing['price'])

# Define the features

features = {'bedrooms':np.array(housing['bedrooms']),

'bathrooms':np.array(housing['bathrooms'])}

return features, labels

Excellent work! In the next exercise, we’ll use the feature columns and data input function to define and train an estimator.

In the previous exercise, you defined a list of feature columns,

feature_list

, and a data input function,

input_fn()

. In this exercise, you will build on that work by defining an

estimator

that makes use of input data.

# Define the model and set the number of steps

model = estimator.DNNRegressor(feature_columns=feature_list, hidden_units=[2,2])

model.train(input_fn, steps=1)

INFO:tensorflow:Using default config.

WARNING:tensorflow:Using temporary folder as model directory: /tmp/tmpwdsztbla

INFO:tensorflow:Using config: {'_model_dir': '/tmp/tmpwdsztbla', '_tf_random_seed': None, '_save_summary_steps': 100, '_save_checkpoints_steps': None, '_save_checkpoints_secs': 600, '_session_config': allow_soft_placement: true

graph_options {

rewrite_options {

meta_optimizer_iterations: ONE

}

}

, '_keep_checkpoint_max': 5, '_keep_checkpoint_every_n_hours': 10000, '_log_step_count_steps': 100, '_train_distribute': None, '_device_fn': None, '_protocol': None, '_eval_distribute': None, '_experimental_distribute': None, '_experimental_max_worker_delay_secs': None, '_session_creation_timeout_secs': 7200, '_service': None, '_cluster_spec': ClusterSpec({}), '_task_type': 'worker', '_task_id': 0, '_global_id_in_cluster': 0, '_master': '', '_evaluation_master': '', '_is_chief': True, '_num_ps_replicas': 0, '_num_worker_replicas': 1}

WARNING:tensorflow:From /usr/local/lib/python3.6/dist-packages/tensorflow_core/python/ops/resource_variable_ops.py:1635: calling BaseResourceVariable.__init__ (from tensorflow.python.ops.resource_variable_ops) with constraint is deprecated and will be removed in a future version.

Instructions for updating:

If using Keras pass *_constraint arguments to layers.

WARNING:tensorflow:From /usr/local/lib/python3.6/dist-packages/tensorflow_core/python/training/training_util.py:236: Variable.initialized_value (from tensorflow.python.ops.variables) is deprecated and will be removed in a future version.

Instructions for updating:

Use Variable.read_value. Variables in 2.X are initialized automatically both in eager and graph (inside tf.defun) contexts.

INFO:tensorflow:Calling model_fn.

WARNING:tensorflow:Layer dnn is casting an input tensor from dtype float64 to the layer's dtype of float32, which is new behavior in TensorFlow 2. The layer has dtype float32 because it's dtype defaults to floatx.

If you intended to run this layer in float32, you can safely ignore this warning. If in doubt, this warning is likely only an issue if you are porting a TensorFlow 1.X model to TensorFlow 2.

To change all layers to have dtype float64 by default, call `tf.keras.backend.set_floatx('float64')`. To change just this layer, pass dtype='float64' to the layer constructor. If you are the author of this layer, you can disable autocasting by passing autocast=False to the base Layer constructor.

WARNING:tensorflow:From /usr/local/lib/python3.6/dist-packages/tensorflow_core/python/keras/optimizer_v2/adagrad.py:103: calling Constant.__init__ (from tensorflow.python.ops.init_ops) with dtype is deprecated and will be removed in a future version.

Instructions for updating:

Call initializer instance with the dtype argument instead of passing it to the constructor

INFO:tensorflow:Done calling model_fn.

INFO:tensorflow:Create CheckpointSaverHook.

INFO:tensorflow:Graph was finalized.

INFO:tensorflow:Running local_init_op.

INFO:tensorflow:Done running local_init_op.

INFO:tensorflow:Saving checkpoints for 0 into /tmp/tmpwdsztbla/model.ckpt.

INFO:tensorflow:loss = 426469720000.0, step = 0

INFO:tensorflow:Saving checkpoints for 1 into /tmp/tmpwdsztbla/model.ckpt.

INFO:tensorflow:Loss for final step: 426469720000.0.

# Define the model and set the number of steps

model = estimator.LinearRegressor(feature_columns=feature_list)

model.train(input_fn, steps=2)

Great work! Note that you have other premade

estimator

options, such as

BoostedTreesRegressor()

, and can also create your own custom estimators.

### Congratulations!

Thank you for reading and hope you’ve learned a lot.