This is the memo of Exploratory Data Analysis in Python from DataCamp.

You can find the original course HERE .

### Course Description

How do we get from data to answers? Exploratory data analysis is a process for exploring datasets, answering questions, and visualizing results. This course presents the tools you need to clean and validate data, to visualize distributions and relationships between variables, and to use regression models to predict and explain. You’ll explore data related to demographics and health, including the National Survey of Family Growth and the General Social Survey. But the methods you learn apply to all areas of science, engineering, and business. You’ll use Pandas, a powerful library for working with data, and other core Python libraries including NumPy and SciPy, StatsModels for regression, and Matplotlib for visualization. With these tools and skills, you will be prepared to work with real data, make discoveries, and present compelling results.

### Table of contents

What’s the average birth weight for babies in the US?

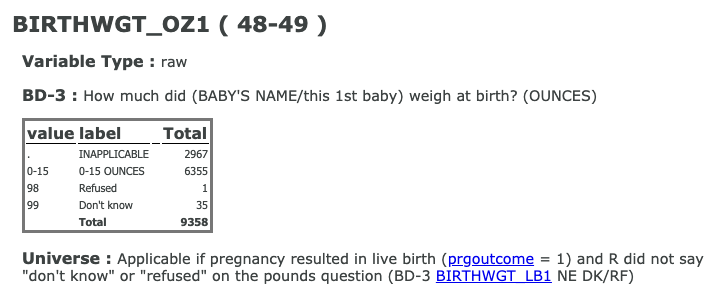

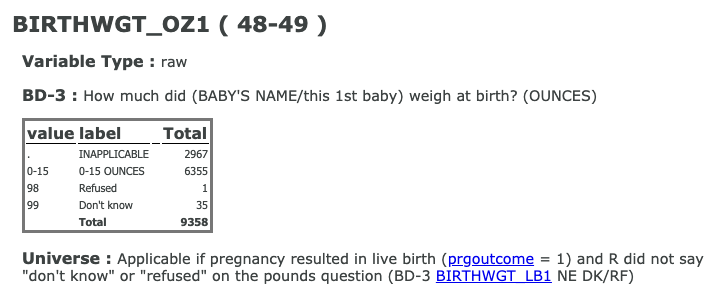

When you work with datasets like the NSFG, it is important to read the documentation carefully. If you interpret a variable incorrectly, you can generate nonsense results and never realize it. So, before we start coding, I want to make sure you are familiar with the NSFG codebook, which describes every variable.

How many respondents refused to answer this question?

1

# Display the number of rows and columns

nsfg.shape

# (9358, 10)

# Display the names of the columns

nsfg.columns

# Index(['caseid', 'outcome', 'birthwgt_lb1', 'birthwgt_oz1', 'prglngth', 'nbrnaliv', 'agecon', 'agepreg', 'hpagelb', 'wgt2013_2015'], dtype='object')

# Select column birthwgt_oz1: ounces

ounces = nsfg['birthwgt_oz1']

# Print the first 5 elements of ounces

print(ounces.head())

nsfg.head()

caseid outcome birthwgt_lb1 birthwgt_oz1 prglngth nbrnaliv agecon agepreg hpagelb wgt2013_2015

0 60418 1 5.0 4.0 40 1.0 2000 2075.0 22.0 3554.964843

1 60418 1 4.0 12.0 36 1.0 2291 2358.0 25.0 3554.964843

2 60418 1 5.0 4.0 36 1.0 3241 3308.0 52.0 3554.964843

3 60419 6 NaN NaN 33 NaN 3650 NaN NaN 2484.535358

4 60420 1 8.0 13.0 41 1.0 2191 2266.0 24.0 2903.782914

In the NSFG dataset, the variable

'outcome'

encodes the outcome of each pregnancy as shown below:

| value | label | | — | — | | 1 | Live birth | | 2 | Induced abortion | | 3 | Stillbirth | | 4 | Miscarriage | | 5 | Ectopic pregnancy | | 6 | Current pregnancy |

The

nsfg

DataFrame has been pre-loaded for you. Explore it in the IPython Shell and use the methods Allen showed you in the video to answer the following question: How many pregnancies in this dataset ended with a live birth?

nsfg.outcome.value_counts()

1 6489

4 1469

2 947

6 249

5 118

3 86

Name: outcome, dtype: int64

In the NSFG dataset, the variable

'nbrnaliv'

records the number of babies born alive at the end of a pregnancy.

If you use

.value_counts()

to view the responses, you’ll see that the value

8

appears once, and if you consult the codebook, you’ll see that this value indicates that the respondent refused to answer the question.

Your job in this exercise is to replace this value with

np.nan

. Recall from the video how Allen replaced the values

98

and

99

in the

ounces

column using the

.replace()

method:

ounces.replace([98, 99], np.nan, inplace=True)

# Replace the value 8 with NaN

nsfg['nbrnaliv'].replace([8], np.nan, inplace=True)

# Print the values and their frequencies

print(nsfg['nbrnaliv'].value_counts())

1.0 6379

2.0 100

3.0 5

Name: nbrnaliv, dtype: int64

If you are careful about this kind of cleaning and validation, it will save time (in the long run) and avoid potentially serious errors.

For each pregnancy in the NSFG dataset, the variable

'agecon'

encodes the respondent’s age at conception, and

'agepreg'

the respondent’s age at the end of the pregnancy.

Both variables are recorded as integers with two implicit decimal places, so the value

2575

means that the respondent’s age was

25.75

.

# Select the columns and divide by 100

agecon = nsfg['agecon'] / 100

agepreg = nsfg['agepreg'] / 100

# Compute the difference

preg_length = agepreg - agecon

# Compute summary statistics

print(preg_length.describe())

count 9109.000000

mean 0.552069

std 0.271479

min 0.000000

25% 0.250000

50% 0.670000

75% 0.750000

max 0.920000

dtype: float64

Histograms are one of the most useful tools in exploratory data analysis. They quickly give you an overview of the distribution of a variable, that is, what values the variable can have, and how many times each value appears.

As we saw in a previous exercise, the NSFG dataset includes a variable

'agecon'

that records age at conception for each pregnancy. Here, you’re going to plot a histogram of this variable. You’ll use the

bins

parameter that you saw in the video, and also a new parameter –

histtype

– which you can read more about

here

in the

matplotlib

documentation. Learning how to read documentation is an essential skill. If you want to learn more about

matplotlib

, you can check out DataCamp’s

Introduction to Matplotlib

course.

# Plot the histogram

plt.hist(agecon, bins=20)

# Label the axes

plt.xlabel('Age at conception')

plt.ylabel('Number of pregnancies')

# Show the figure

plt.show()

# Plot the histogram

plt.hist(agecon, bins=20, histtype='step')

# Label the axes

plt.xlabel('Age at conception')

plt.ylabel('Number of pregnancies')

# Show the figure

plt.show()

Now let’s pull together the steps in this chapter to compute the average birth weight for full-term babies.

I’ve provided a function,

resample_rows_weighted

, that takes the NSFG data and resamples it using the sampling weights in

wgt2013_2015

. The result is a sample that is representative of the U.S. population.

Then I extract

birthwgt_lb1

and

birthwgt_oz1

, replace special codes with

NaN

, and compute total birth weight in pounds,

birth_weight

.

# Resample the data

nsfg = resample_rows_weighted(nsfg, 'wgt2013_2015')

# Clean the weight variables

pounds = nsfg['birthwgt_lb1'].replace([98, 99], np.nan)

ounces = nsfg['birthwgt_oz1'].replace([98, 99], np.nan)

# Compute total birth weight

birth_weight = pounds + ounces/16

# Create a Boolean Series for full-term babies

full_term = nsfg.prglngth >=37

# Select the weights of full-term babies

full_term_weight = birth_weight[full_term]

# Compute the mean weight of full-term babies

print(np.mean(full_term_weight))

# 7.392597951914515

In the previous exercise, you computed the mean birth weight for full-term babies; you filtered out preterm babies because their distribution of weight is different.

The distribution of weight is also different for multiple births, like twins and triplets. In this exercise, you’ll filter them out, too, and see what effect it has on the mean.

# Filter full-term babies

full_term = nsfg['prglngth'] >= 37

# Filter single births

single = nsfg['nbrnaliv'] == 1

# Compute birth weight for single full-term babies

single_full_term_weight = birth_weight[single & full_term]

print('Single full-term mean:', single_full_term_weight.mean())

# Single full-term mean: 7.40297320308299

# Compute birth weight for multiple full-term babies

mult_full_term_weight = birth_weight[~single & full_term]

print('Multiple full-term mean:', mult_full_term_weight.mean())

# Multiple full-term mean: 5.784722222222222

The GSS dataset has been pre-loaded for you into a DataFrame called

gss

. You can explore it in the IPython Shell to get familiar with it.

In this exercise, you’ll focus on one variable in this dataset,

'year'

, which represents the year each respondent was interviewed.

The

Pmf

class you saw in the video has already been created for you. You can access it outside of DataCamp via the

empiricaldist

library.

gss

year sex age cohort race educ realinc wtssall

0 1972 1 26.0 1946.0 1 18.0 13537.0000 0.889300

1 1972 2 38.0 1934.0 1 12.0 18951.0000 0.444600

... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

62462 2016 2 61.0 1955.0 1 16.0 65520.0000 0.956994

62463 2016 2 67.0 1949.0 1 13.0 NaN 1.564363

62464 2016 2 57.0 1959.0 1 12.0 9945.0000 0.956994

62465 2016 2 56.0 1960.0 1 12.0 38610.0000 0.478497

[62466 rows x 8 columns]

# Compute the PMF for year

pmf_year = Pmf(gss.year, normalize=False)

# Print the result

print(pmf_year)

1972 1613

1973 1504

...

2014 2538

2016 2867

Name: Pmf, dtype: int64

Now let’s plot a PMF for the age of the respondents in the GSS dataset. The variable

'age'

contains respondents’ age in years.

# Select the age column

age = gss['age']

# Make a PMF of age

pmf_age = Pmf(age)

# Plot the PMF

pmf_age.bar()

# Label the axes

plt.xlabel('Age')

plt.ylabel('PMF')

plt.show()

In this exercise, you’ll make a CDF and use it to determine the fraction of respondents in the GSS dataset who are OLDER than 30.

The GSS dataset has been preloaded for you into a DataFrame called

gss

.

As with the

Pmf

class from the previous lesson, the

Cdf

class you just saw in the video has been created for you, and you can access it outside of DataCamp via the

empiricaldist

library.

# Select the age column

age = gss['age']

# Compute the CDF of age

cdf_age = Cdf(age)

# Calculate the CDF of 30

print(cdf_age[30])

# 0.2539137136526388

Recall from the video that the interquartile range (IQR) is the difference between the 75th and 25th percentiles. It is a measure of variability that is robust in the presence of errors or extreme values.

In this exercise, you’ll compute the interquartile range of income in the GSS dataset. Income is stored in the

'realinc'

column, and the CDF of income has already been computed and stored in

cdf_income

.

np.percentile(gss.realinc.sort_values().dropna(),75)

# 43426.0

cdf_income.inverse(0.75)

# array(43426.)

# Calculate the 75th percentile

percentile_75th = cdf_income.inverse(0.75)

# Calculate the 25th percentile

percentile_25th = cdf_income.inverse(0.25)

# Calculate the interquartile range

iqr = percentile_75th - percentile_25th

# Print the interquartile range

print(iqr)

The distribution of income in almost every country is long-tailed; that is, there are a small number of people with very high incomes.

In the GSS dataset, the variable

'realinc'

represents total household income, converted to 1986 dollars. We can get a sense of the shape of this distribution by plotting the CDF.

# Select realinc

income = gss.realinc

# Make the CDF

cdf_income = Cdf(income)

# Plot it

cdf_income.plot()

# Label the axes

plt.xlabel('Income (1986 USD)')

plt.ylabel('CDF')

plt.show()

Let’s begin comparing incomes for different levels of education in the GSS dataset, which has been pre-loaded for you into a DataFrame called

gss

. The variable

educ

represents the respondent’s years of education.

What fraction of respondents report that they have 12 years of education or fewer?

Cdf(gss.educ)

0.0 0.002311

1.0 0.002921

...

12.0 0.532261

...

19.0 0.979231

20.0 1.000000

Name: Cdf, dtype: float64

Cdf(gss.educ)(12)

# array(0.53226117)

Let’s create Boolean Series to identify respondents with different levels of education.

In the U.S, 12 years of education usually means the respondent has completed high school (secondary education). A respondent with 14 years of education has probably completed an associate degree (two years of college); someone with 16 years has probably completed a bachelor’s degree (four years of college).

# Select educ

educ = gss['educ']

# Bachelor's degree

bach = (educ >= 16)

# Associate degree

assc = (educ >= 14) & (educ < 16)

# High school (12 or fewer years of education)

high = (educ <= 12)

print(high.mean())

# 0.5308807991547402

Let’s now see what the distribution of income looks like for people with different education levels. You can do this by plotting the CDFs. Recall how Allen plotted the income CDFs of respondents interviewed before and after 1995:

Cdf(income[pre95]).plot(label='Before 1995')

Cdf(income[~pre95]).plot(label='After 1995')

You can assume that Boolean Series have been defined, as in the previous exercise, to identify respondents with different education levels:

high

,

assc

, and

bach

.

income = gss['realinc']

# Plot the CDFs

Cdf(income[high]).plot(label='High school')

Cdf(income[assc]).plot(label='Associate')

Cdf(income[bach]).plot(label='Bachelor')

# Label the axes

plt.xlabel('Income (1986 USD)')

plt.ylabel('CDF')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

It might not be surprising that people with more education have higher incomes, but looking at these distributions, we can see where the differences are.

In many datasets, the distribution of income is approximately lognormal, which means that the logarithms of the incomes fit a normal distribution. We’ll see whether that’s true for the GSS data. As a first step, you’ll compute the mean and standard deviation of the log of incomes using NumPy’s

np.log10()

function.

Then, you’ll use the computed mean and standard deviation to make a

norm

object using the

scipy.stats.norm()

function.

# Extract realinc and compute its log

income = gss['realinc']

log_income = np.log10(income)

# Compute mean and standard deviation

mean = np.mean(log_income)

std = np.std(log_income)

print(mean, std)

# 4.371148677934171 0.42900437330100427

# Make a norm object

from scipy.stats import norm

dist = norm(mean,std)

To see whether the distribution of income is well modeled by a lognormal distribution, we’ll compare the CDF of the logarithm of the data to a normal distribution with the same mean and standard deviation.

dist

is a

scipy.stats.norm

object with the same mean and standard deviation as the data. It provides

.cdf()

, which evaluates the normal cumulative distribution function.

Be careful with capitalization:

Cdf()

, with an uppercase

C

, creates

Cdf

objects.

dist.cdf()

, with a lowercase

c

, evaluates the normal cumulative distribution function.

# Evaluate the model CDF

xs = np.linspace(2, 5.5)

ys = dist.cdf(xs)

# Plot the model CDF

plt.clf()

plt.plot(xs, ys, color='gray')

# Create and plot the Cdf of log_income

Cdf(log_income).plot()

# Label the axes

plt.xlabel('log10 of realinc')

plt.ylabel('CDF')

plt.show()

The lognormal model is a pretty good fit for the data, but clearly not a perfect match. That’s what real data is like; sometimes it doesn’t fit the model.

In the previous exercise, we used CDFs to see if the distribution of income is lognormal. We can make the same comparison using a PDF and KDE. That’s what you’ll do in this exercise!

Just as all

norm

objects have a

.cdf()

method, they also have a

.pdf()

method.

To create a KDE plot, you can use Seaborn’s

kdeplot()

function. To learn more about this function and Seaborn, you can check out DataCamp’s

Data Visualization with Seaborn

course. Here, Seaborn has been imported for you as

sns

.

# Evaluate the normal PDF

xs = np.linspace(2, 5.5)

ys = dist.pdf(xs)

# Plot the model PDF

plt.clf()

plt.plot(xs, ys, color='gray')

# Plot the data KDE

sns.kdeplot(log_income)

# Label the axes

plt.xlabel('log10 of realinc')

plt.ylabel('PDF')

plt.show()

Do people tend to gain weight as they get older? We can answer this question by visualizing the relationship between weight and age. But before we make a scatter plot, it is a good idea to visualize distributions one variable at a time. Here, you’ll visualize age using a bar chart first. Recall that all PMF objects have a

.bar()

method to make a bar chart.

The BRFSS dataset includes a variable,

'AGE'

(note the capitalization!), which represents each respondent’s age. To protect respondents’ privacy, ages are rounded off into 5-year bins.

'AGE'

contains the midpoint of the bins.

# Extract age

age = brfss.AGE

# Plot the PMF

Pmf(age).bar()

# Label the axes

plt.xlabel('Age in years')

plt.ylabel('PMF')

plt.show()

Now let’s make a scatterplot of

weight

versus

age

. To make the code run faster, I’ve selected only the first 1000 rows from the

brfss

DataFrame.

weight

and

age

have already been extracted for you. Your job is to use

plt.plot()

to make a scatter plot.

# Select the first 1000 respondents

brfss = brfss[:1000]

# Extract age and weight

age = brfss['AGE']

weight = brfss['WTKG3']

# Make a scatter plot

plt.plot(age,weight,'o',alpha=0.1)

plt.xlabel('Age in years')

plt.ylabel('Weight in kg')

plt.show()

In the previous exercise, the ages fall in columns because they’ve been rounded into 5-year bins. If we jitter them, the scatter plot will show the relationship more clearly. Recall how Allen jittered

height

and

weight

in the video:

height_jitter = height + np.random.normal(0, 2, size=len(brfss))

weight_jitter = weight + np.random.normal(0, 2, size=len(brfss))

# Select the first 1000 respondents

brfss = brfss[:1000]

# Add jittering to age

age = brfss['AGE'] + np.random.normal(0,2.5,size=len(brfss))

# Extract weight

weight = brfss['WTKG3']

# Make a scatter plot

plt.plot(age,weight,'o',alpha=0.2,markersize=5)

plt.xlabel('Age in years')

plt.ylabel('Weight in kg')

plt.show()

By smoothing out the ages and avoiding saturation, we get the best view of the data. But in this case the nature of the relationship is still hard to see.

Previously we looked at a scatter plot of height and weight, and saw that taller people tend to be heavier. Now let’s take a closer look using a box plot. The

brfss

DataFrame contains a variable

'_HTMG10'

that represents height in centimeters, binned into 10 cm groups.

Recall how Allen created the box plot of

'AGE'

and

'WTKG3'

in the video, with the y-axis on a logarithmic scale:

sns.boxplot(x='AGE', y='WTKG3', data=data, whis=10)

plt.yscale('log')

# Drop rows with missing data

data = brfss.dropna(subset=['_HTMG10', 'WTKG3'])

# Make a box plot

sns.boxplot('_HTMG10','WTKG3',whis=10,data=data)

# Plot the y-axis on a log scale

plt.yscale('log')

# Remove unneeded lines and label axes

sns.despine(left=True, bottom=True)

plt.xlabel('Height in cm')

plt.ylabel('Weight in kg')

plt.show()

In the next two exercises we’ll look at relationships between income and other variables. In the BRFSS, income is represented as a categorical variable; that is, respondents are assigned to one of 8 income categories. The variable name is

'INCOME2'

. Before we connect income with anything else, let’s look at the distribution by computing the PMF. Recall that all

Pmf

objects have a

.bar()

method.

# Extract income

income = brfss.INCOME2

# Plot the PMF

Pmf(income).bar()

# Label the axes

plt.xlabel('Income level')

plt.ylabel('PMF')

plt.show()

Almost half of the respondents are in the top income category, so this dataset doesn’t distinguish between the highest incomes and the median. But maybe it can tell us something about people with incomes below the median.

Let’s now use a violin plot to visualize the relationship between income and height.

# Drop rows with missing data

data = brfss.dropna(subset=['INCOME2', 'HTM4'])

# Make a violin plot

sns.violinplot('INCOME2','HTM4',inner=None,data=data)

# Remove unneeded lines and label axes

sns.despine(left=True, bottom=True)

plt.xlabel('Income level')

plt.ylabel('Height in cm')

plt.show()

It looks like there is a weak positive relationsip between income and height, at least for incomes below the median.

The purpose of the BRFSS is to explore health risk factors, so it includes questions about diet. The variable

'_VEGESU1'

represents the number of servings of vegetables respondents reported eating per day.

Let’s see how this variable relates to age and income.

# Select columns

columns = ['AGE', 'INCOME2', '_VEGESU1']

subset = brfss[columns]

# Compute the correlation matrix

print(subset.corr())

AGE INCOME2 _VEGESU1

AGE 1.000000 -0.015158 -0.009834

INCOME2 -0.015158 1.000000 0.119670

_VEGESU1 -0.009834 0.119670 1.000000

In the previous exercise, the correlation between income and vegetable consumption is about

0.12

. The correlation between age and vegetable consumption is about

-0.01

.

The following are correct interpretations of these results:

The correlation between income and vegetable consumption is small ( 0.12 ), but it suggests that there is a week relationship.

But a correlation( -0.01) close to 0 does mean there is no relationship.

As we saw in a previous exercise, the variable

'_VEGESU1'

represents the number of vegetable servings respondents reported eating per day.

Let’s estimate the slope of the relationship between vegetable consumption and income.

from scipy.stats import linregress

# Extract the variables

subset = brfss.dropna(subset=['INCOME2', '_VEGESU1'])

xs = subset['INCOME2']

ys = subset['_VEGESU1']

# Compute the linear regression

res = linregress(xs,ys)

print(res)

LinregressResult(slope=0.06988048092105019, intercept=1.5287786243363106, rvalue=0.11967005884864107, pvalue=1.378503916247615e-238, stderr=0.002110976356332332)

# rvalue: correlation coefficient

Continuing from the previous exercise:

xs

and

ys

contain income codes and daily vegetable consumption, respectively, andres

contains the results of a simple linear regression of

ys

onto

xs

.Now, you’re going to compute the line of best fit. NumPy has been imported for you as

np

.

# Plot the scatter plot

plt.clf()

x_jitter = xs + np.random.normal(0, 0.15, len(xs))

plt.plot(x_jitter, ys, 'o', alpha=0.2)

# Plot the line of best fit

fx = np.array([xs.min(), xs.max()])

fy = res.slope * fx + res.intercept

plt.plot(fx, fy, '-', alpha=0.7)

plt.xlabel('Income code')

plt.ylabel('Vegetable servings per day')

plt.ylim([0, 6])

plt.show()

In the BRFSS dataset, there is a strong relationship between vegetable consumption and income. The income of people who eat 8 servings of vegetables per day is double the income of people who eat none, on average.

Which of the following conclusions can we draw from this data?

None of them.

This data is consistent with all of these conclusions, but it does not provide conclusive evidence for any of them.

Let’s run the same regression using SciPy and StatsModels, and confirm we get the same results.

from scipy.stats import linregress

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

# Run regression with linregress

subset = brfss.dropna(subset=['INCOME2', '_VEGESU1'])

xs = subset['INCOME2']

ys = subset['_VEGESU1']

res = linregress(xs,ys)

print(res)

# Run regression with StatsModels

results = smf.ols('_VEGESU1 ~ INCOME2', data = brfss).fit()

print(results.params)

LinregressResult(slope=0.06988048092105019, intercept=1.5287786243363106, rvalue=0.11967005884864107, pvalue=1.378503916247615e-238, stderr=0.002110976356332332)

Intercept 1.528779

INCOME2 0.069880

dtype: float64

When you start working with a new library, checks like this help ensure that you are doing it right.

To get a closer look at the relationship between income and education, let’s use the variable

'educ'

to group the data, then plot mean income in each group.

# Group by educ

grouped = gss.groupby('educ')

# Compute mean income in each group

mean_income_by_educ = grouped['realinc'].mean()

# Plot mean income as a scatter plot

plt.plot(mean_income_by_educ, 'o', alpha=0.5)

# Label the axes

plt.xlabel('Education (years)')

plt.ylabel('Income (1986 $)')

plt.show()

The graph in the previous exercise suggests that the relationship between income and education is non-linear. So let’s try fitting a non-linear model.

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

# Add a new column with educ squared

gss['educ2'] = gss['educ'] ** 2

# Run a regression model with educ, educ2, age, and age2

results = smf.ols('realinc ~ educ + educ2 + age + age2',data=gss).fit()

# Print the estimated parameters

print(results.params)

Intercept -23241.884034

educ -528.309369

educ2 159.966740

age 1696.717149

age2 -17.196984

dtype: float64

The slope associated with

educ2

is positive, so the model curves upward.

At this point, we have a model that predicts income using age, education, and sex.

Let’s see what it predicts for different levels of education, holding

age

constant.

# Run a regression model with educ, educ2, age, and age2

results = smf.ols('realinc ~ educ + educ2 + age + age2', data=gss).fit()

# Make the DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame()

df['educ'] = np.linspace(0,20)

df['age'] = 30

df['educ2'] = df['educ']**2

df['age2'] = df['age']**2

# Generate and plot the predictions

pred = results.predict(df)

print(pred.head())

0 12182.344976

1 11993.358518

2 11857.672098

3 11775.285717

4 11746.199374

dtype: float64

Now let’s visualize the results from the previous exercise!

# Plot mean income in each age group

plt.clf()

grouped = gss.groupby('educ')

mean_income_by_educ = grouped['realinc'].mean()

plt.plot(mean_income_by_educ,'o',alpha=0.5)

# Plot the predictions

pred = results.predict(df)

plt.plot(df['educ'], pred, label='Age 30')

# Label axes

plt.xlabel('Education (years)')

plt.ylabel('Income (1986 $)')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Looks like this model captures the relationship pretty well.

Let’s use logistic regression to predict a binary variable. Specifically, we’ll use age, sex, and education level to predict support for legalizing cannabis (marijuana) in the U.S.

In the GSS dataset, the variable

grass

records the answer to the question “Do you think the use of marijuana should be made legal or not?”

# Recode grass

gss['grass'].replace(2, 0, inplace=True)

# Run logistic regression

results = smf.logit('grass ~ age + age2 + educ + educ2 + C(sex)', data=gss).fit()

results.params

Intercept -1.685223

C(sex)[T.2] -0.384611

age -0.034756

age2 0.000192

educ 0.221860

educ2 -0.004163

dtype: float64

# Make a DataFrame with a range of ages

df = pd.DataFrame()

df['age'] = np.linspace(18, 89)

df['age2'] = df['age']**2

# Set the education level to 12

df['educ'] = 12

df['educ2'] = df['educ']**2

# Generate predictions for men and women

df['sex'] = 1

pred1 = results.predict(df)

df['sex'] = 2

pred2 = results.predict(df)

grouped = gss.groupby('age')

favor_by_age = grouped['grass'].mean()

plt.clf()

plt.plot(favor_by_age, 'o', alpha=0.5)

plt.plot(df['age'], pred1, label='Male')

plt.plot(df['age'], pred2, label='Female')

plt.xlabel('Age')

plt.ylabel('Probability of favoring legalization')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Thank you for reading and hope you’ve learned a lot.