This is the memo of the 25th course of ‘Data Scientist with Python’ track.

You can find the original course HERE .

#### Coding the forward propagation algorithm

In this exercise, you’ll write code to do forward propagation (prediction) for your first neural network:

Each data point is a customer. The first input is how many accounts they have, and the second input is how many children they have. The model will predict how many transactions the user makes in the next year.

You will use this data throughout the first 2 chapters of this course.

input_data

# array([3, 5])

weights

# {'node_0': array([2, 4]), 'node_1': array([ 4, -5]), 'output': array([2, 7])}

input_data * weights['node_0']

# array([ 6, 20])

np.array([3, 5]) * np.array([2, 4])

# array([ 6, 20])

(input_data * weights['node_0']).sum()

# 26

# Calculate node 0 value: node_0_value

node_0_value = (input_data * weights['node_0']).sum()

# Calculate node 1 value: node_1_value

node_1_value = (input_data * weights['node_1']).sum()

# Put node values into array: hidden_layer_outputs

hidden_layer_outputs = np.array([node_0_value, node_1_value])

# Calculate output: output

output = (hidden_layer_outputs * weights['output']).sum()

# Print output

print(output)

# -39

It looks like the network generated a prediction of

-39

.

#### The Rectified Linear Activation Function

An “activation function” is a function applied at each node. It converts the node’s input into some output.

The rectified linear activation function (called ReLU ) has been shown to lead to very high-performance networks. This function takes a single number as an input, returning 0 if the input is negative, and the input if the input is positive.

Here are some examples:

relu(3) = 3

relu(-3) = 0

def relu(input):

'''Define your relu activation function here'''

# Calculate the value for the output of the relu function: output

output = max(input, 0)

# Return the value just calculated

return(output)

# Calculate node 0 value: node_0_output

node_0_input = (input_data * weights['node_0']).sum()

node_0_output = relu(node_0_input)

# Calculate node 1 value: node_1_output

node_1_input = (input_data * weights['node_1']).sum()

node_1_output = relu(node_1_input)

# Put node values into array: hidden_layer_outputs

hidden_layer_outputs = np.array([node_0_output, node_1_output])

# Calculate model output (do not apply relu)

model_output = (hidden_layer_outputs * weights['output']).sum()

# Print model output

print(model_output)

# 52

You predicted 52 transactions. Without this activation function, you would have predicted a negative number!

The real power of activation functions will come soon when you start tuning model weights.

#### Applying the network to many observations/rows of data

input_data

[array([3, 5]), array([ 1, -1]), array([0, 0]), array([8, 4])]

weights

{'node_0': array([2, 4]), 'node_1': array([ 4, -5]), 'output': array([2, 7])}

def relu(input):

'''Define relu activation function'''

return(max(input, 0))

# Define predict_with_network()

def predict_with_network(input_data_row, weights):

# Calculate node 0 value

node_0_input = (input_data_row * weights['node_0']).sum()

node_0_output = relu(node_0_input)

# Calculate node 1 value

node_1_input = (input_data_row * weights['node_1']).sum()

node_1_output = relu(node_1_input)

# Put node values into array: hidden_layer_outputs

hidden_layer_outputs = np.array([node_0_output, node_1_output])

# Calculate model output

input_to_final_layer = (hidden_layer_outputs * weights['output']).sum()

model_output = relu(input_to_final_layer)

# Return model output

return(model_output)

# Create empty list to store prediction results

results = []

for input_data_row in input_data:

# Append prediction to results

results.append(predict_with_network(input_data_row, weights))

# Print results

print(results)

# [52, 63, 0, 148]

#### Forward propagation in a deeper network

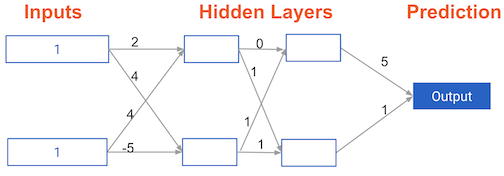

You now have a model with 2 hidden layers. The values for an input data point are shown inside the input nodes. The weights are shown on the edges/lines. What prediction would this model make on this data point?

Assume the activation function at each node is the identity function . That is, each node’s output will be the same as its input. So the value of the bottom node in the first hidden layer is -1, and not 0, as it would be if the ReLU activation function was used.

| Hidden Layer 1 | Hidden Layer 2 | Prediction | | 6 | -1 | | | | | 0 | | -1 | 5 | |

#### Multi-layer neural networks

In this exercise, you’ll write code to do forward propagation for a neural network with 2 hidden layers. Each hidden layer has two nodes.

input_data

array([3, 5])

weights

{'node_0_0': array([2, 4]),

'node_0_1': array([ 4, -5]),

'node_1_0': array([-1, 2]),

'node_1_1': array([1, 2]),

'output': array([2, 7])}

def predict_with_network(input_data):

# Calculate node 0 in the first hidden layer

node_0_0_input = (input_data * weights['node_0_0']).sum()

node_0_0_output = relu(node_0_0_input)

# Calculate node 1 in the first hidden layer

node_0_1_input = (input_data * weights['node_0_1']).sum()

node_0_1_output = relu(node_0_1_input)

# Put node values into array: hidden_0_outputs

hidden_0_outputs = np.array([node_0_0_output, node_0_1_output])

# Calculate node 0 in the second hidden layer

node_1_0_input = (hidden_0_outputs * weights['node_1_0']).sum()

node_1_0_output = relu(node_1_0_input)

# Calculate node 1 in the second hidden layer

node_1_1_input = (hidden_0_outputs * weights['node_1_1']).sum()

node_1_1_output = relu(node_1_1_input)

# Put node values into array: hidden_1_outputs

hidden_1_outputs = np.array([node_1_0_output, node_1_1_output])

# Calculate model output: model_output

model_output = (hidden_1_outputs * weights['output']).sum()

# Return model_output

return(model_output)

output = predict_with_network(input_data)

print(output)

# 182

#### Representations are learned

How are the weights that determine the features/interactions in Neural Networks created?

The model training process sets them to optimize predictive accuracy.

#### Levels of representation

Which layers of a model capture more complex or “higher level” interactions?

The last layers capture the most complex interactions.

#### Calculating model errors

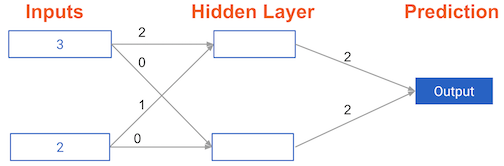

What is the error (predicted – actual) for the following network when the input data is [3, 2] and the actual value of the target (what you are trying to predict) is 5?

prediction = (32 + 21) * 2 + (30 + 20)*2

=16

error = 16 – 5 = 11

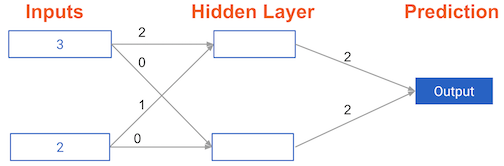

#### Understanding how weights change model accuracy

Imagine you have to make a prediction for a single data point. The actual value of the target is 7. The weight going from

node_0

to the output is 2, as shown below.

If you increased it slightly, changing it to 2.01, would the predictions become more accurate, less accurate, or stay the same?

prediction_before = 16

error_before = 16 – 7 = 9

prediction_after = (32.01 + 21) * 2 + (30 + 20)*2

=16.x

error_after = 9.x

Increasing the weight to

2.01

would increase the resulting error from

9

to

9.08

, making the predictions

less

accurate.

#### Coding how weight changes affect accuracy

Now you’ll get to change weights in a real network and see how they affect model accuracy!

Have a look at the following neural network:

weights_0weights_0weights_1target_actual

# The data point you will make a prediction for

input_data = np.array([0, 3])

# Sample weights

weights_0 = {'node_0': [2, 1],

'node_1': [1, 2],

'output': [1, 1]

}

# The actual target value, used to calculate the error

target_actual = 3

# Make prediction using original weights

model_output_0 = predict_with_network(input_data, weights_0)

# Calculate error: error_0

error_0 = model_output_0 - target_actual

# Create weights that cause the network to make perfect prediction (3): weights_1

weights_1 = {'node_0': [2, 1],

'node_1': [1, 2],

'output': [1, 0]

}

# Make prediction using new weights: model_output_1

model_output_1 = predict_with_network(input_data, weights_1)

# Calculate error: error_1

error_1 = model_output_1 - target_actual

# Print error_0 and error_1

print(error_0)

print(error_1)

# 6

# 0

#### Scaling up to multiple data points

You’ve seen how different weights will have different accuracies on a single prediction. But usually, you’ll want to measure model accuracy on many points.

You’ll now write code to compare model accuracies for two different sets of weights, which have been stored as

weights_0

and

weights_1

.

input_data

[array([0, 3]), array([1, 2]), array([-1, -2]), array([4, 0])]

target_actuals

[1, 3, 5, 7]

weights_0

{'node_0': array([2, 1]), 'node_1': array([1, 2]), 'output': array([1, 1])}

weights_1

{'node_0': array([2, 1]),

'node_1': array([1. , 1.5]),

'output': array([1. , 1.5])}

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

# Create model_output_0

model_output_0 = []

# Create model_output_1

model_output_1 = []

# Loop over input_data

for row in input_data:

# Append prediction to model_output_0

model_output_0.append(predict_with_network(row, weights_0))

# Append prediction to model_output_1

model_output_1.append(predict_with_network(row, weights_1))

# Calculate the mean squared error for model_output_0: mse_0

mse_0 = mean_squared_error(target_actuals, model_output_0)

# Calculate the mean squared error for model_output_1: mse_1

mse_1 = mean_squared_error(target_actuals, model_output_1)

# Print mse_0 and mse_1

print("Mean squared error with weights_0: %f" %mse_0)

print("Mean squared error with weights_1: %f" %mse_1)

# Mean squared error with weights_0: 37.500000

# Mean squared error with weights_1: 49.890625

It looks like

model_output_1

has a higher mean squared error.

ex. learning rate = 0.01

w.r.t. = with respect to

new weight = 2 – -24 * 0.01 = 2.24

#### Calculating slopes

You’re now going to practice calculating slopes.

When plotting the mean-squared error loss function against predictions, the slope is

2 * x * (y-xb)

, or

2 * input_data * error

.

Note that

x

and

b

may have multiple numbers (

x

is a vector for each data point, and

b

is a vector). In this case, the output will also be a vector, which is exactly what you want.

You’re ready to write the code to calculate this slope while using a single data point.

input_data

array([1, 2, 3])

weights

array([0, 2, 1])

target

0

# Calculate the predictions: preds

preds = (weights * input_data).sum()

# Calculate the error: error

error = target - preds

# Calculate the slope: slope

slope = 2 * input_data * error

# Print the slope

print(slope)

# [-14 -28 -42]

You can now use this slope to improve the weights of the model!

#### Improving model weights

You’ve just calculated the slopes you need. Now it’s time to use those slopes to improve your model.

If you add the slopes to your weights, you will move in the right direction. However, it’s possible to move too far in that direction.

So you will want to take a small step in that direction first, using a lower learning rate, and verify that the model is improving.

# Set the learning rate: learning_rate

learning_rate = 0.01

# Calculate the predictions: preds

preds = (weights * input_data).sum()

# weights

# array([0, 2, 1])

# Calculate the error: error

error = preds - target

# Calculate the slope: slope

slope = 2 * input_data * error

# slope

# array([14, 28, 42])

# Update the weights: weights_updated

weights_updated = weights - learning_rate * slope

# weights_updated

# array([-0.14, 1.72, 0.58])

# Get updated predictions: preds_updated

preds_updated = (weights_updated * input_data).sum()

# Calculate updated error: error_updated

error_updated = preds_updated - target

# Print the original error

print(error)

# Print the updated error

print(error_updated)

# 7

# 5.04

Updating the model weights did indeed decrease the error!

#### Making multiple updates to weights

You’re now going to make multiple updates so you can dramatically improve your model weights, and see how the predictions improve with each update.

get_slope?

Signature: get_slope(input_data, target, weights)

Docstring: <no docstring>

File: /tmp/tmpt3wthzls/<ipython-input-1-7b11d278e306>

Type: function

get_mse?

Signature: get_mse(input_data, target, weights)

Docstring: <no docstring>

File: /tmp/tmpt3wthzls/<ipython-input-1-7b11d278e306>

Type: function

n_updates = 20

mse_hist = []

# Iterate over the number of updates

for i in range(n_updates):

# Calculate the slope: slope

slope = get_slope(input_data, target, weights)

# Update the weights: weights

weights = weights - slope * 0.01

# Calculate mse with new weights: mse

mse = get_mse(input_data, target, weights)

# Append the mse to mse_hist

mse_hist.append(mse)

# Plot the mse history

plt.plot(mse_hist)

plt.xlabel('Iterations')

plt.ylabel('Mean Squared Error')

plt.show()

As you can see, the mean squared error decreases as the number of iterations go up.

#### The relationship between forward and backward propagation

If you have gone through 4 iterations of calculating slopes (using backward propagation) and then updated weights.

How many times must you have done forward propagation?

4

Each time you generate predictions using forward propagation, you update the weights using backward propagation.

#### Thinking about backward propagation

If your predictions were all exactly right, and your errors were all exactly 0, the slope of the loss function with respect to your predictions would also be 0.

In that circumstance, the updates to all weights in the network would also be 0.

slope = 2 * imput * error

6 and 18 are slopes just calculated in the above graph

x <= 0: slope = 0

x > 0: slope = 1

gradient = input(white) * slope(red) * ReLU_slope(=1 here)

gradient_0 = 061 = 0

gradient_3 = 1181 = 18

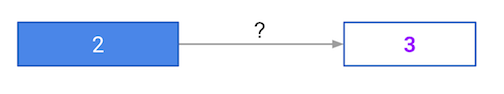

#### A round of backpropagation

In the network shown below, we have done forward propagation, and node values calculated as part of forward propagation are shown in white.

The weights are shown in black.

Layers after the question mark show the slopes calculated as part of back-prop, rather than the forward-prop values. Those slope values are shown in purple.

This network again uses the ReLU activation function, so the slope of the activation function is 1 for any node receiving a positive value as input.

Assume the node being examined had a positive value (so the activation function’s slope is 1).

What is the slope needed to update the weight with the question mark?

gradient = input(white) * slope(purple) * ReLU_slope(=1 here)

= 231 = 6

#### Understanding your data

You will soon start building models in Keras to predict wages based on various professional and demographic factors.

Before you start building a model, it’s good to understand your data by performing some exploratory analysis.

df.head()

wage_per_hour union education_yrs experience_yrs age female marr \

0 5.10 0 8 21 35 1 1

1 4.95 0 9 42 57 1 1

2 6.67 0 12 1 19 0 0

3 4.00 0 12 4 22 0 0

4 7.50 0 12 17 35 0 1

south manufacturing construction

0 0 1 0

1 0 1 0

2 0 1 0

3 0 0 0

4 0 0 0

#### Specifying a model

Now you’ll get to work with your first model in Keras, and will immediately be able to run more complex neural network models on larger datasets compared to the first two chapters.

To start, you’ll take the skeleton of a neural network and add a hidden layer and an output layer. You’ll then fit that model and see Keras do the optimization so your model continually gets better.

predictors[:3]

array([[ 0, 8, 21, 35, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0],

[ 0, 9, 42, 57, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0],

[ 0, 12, 1, 19, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0]])

# Import necessary modules

import keras

from keras.layers import Dense

from keras.models import Sequential

# Save the number of columns in predictors: n_cols

n_cols = predictors.shape[1]

# Set up the model: model

model = Sequential()

# Add the first layer

model.add(Dense(50, activation='relu', input_shape=(n_cols,)))

# Add the second layer

model.add(Dense(32, activation='relu'))

# Add the output layer

model.add(Dense(1))

Now that you’ve specified the model, the next step is to compile it.

#### Compiling the model

You’re now going to compile the model you specified earlier. To compile the model, you need to specify the optimizer and loss function to use.

The Adam optimizer is an excellent choice. You can read more about it as well as other keras optimizers here , and if you are really curious to learn more, you can read the original paper that introduced the Adam optimizer.

In this exercise, you’ll use the Adam optimizer and the mean squared error loss function. Go for it!

# Import necessary modules

import keras

from keras.layers import Dense

from keras.models import Sequential

# Specify the model

n_cols = predictors.shape[1]

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(50, activation='relu', input_shape = (n_cols,)))

model.add(Dense(32, activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(1))

# Compile the model

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='mean_squared_error')

# Verify that model contains information from compiling

print("Loss function: " + model.loss)

# Loss function: mean_squared_error

#### Fitting the model

# Import necessary modules

import keras

from keras.layers import Dense

from keras.models import Sequential

# Specify the model

n_cols = predictors.shape[1]

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(50, activation='relu', input_shape = (n_cols,)))

model.add(Dense(32, activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(1))

# Compile the model

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='mean_squared_error')

# Fit the model

model.fit(predictors, target)

Epoch 1/10

32/534 [>.............................] - ETA: 1s - loss: 146.0927

534/534 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 78.1405

Epoch 2/10

32/534 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 85.0537

534/534 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 30.3265

Epoch 3/10

32/534 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 21.0463

534/534 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 27.0886

Epoch 4/10

32/534 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 16.8466

534/534 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 25.1240

Epoch 5/10

32/534 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 23.2123

534/534 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 24.0247

Epoch 6/10

32/534 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 13.3941

534/534 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 23.2055

Epoch 7/10

32/534 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 28.1707

534/534 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 22.4556

Epoch 8/10

32/534 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 11.3898

534/534 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 22.0805

Epoch 9/10

32/534 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 21.9370

480/534 [=========================>....] - ETA: 0s - loss: 21.9982

534/534 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 21.7470

Epoch 10/10

32/534 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 5.4697

534/534 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 21.5538

<keras.callbacks.History at 0x7f0fc2b49390>

You now know how to specify, compile, and fit a deep learning model using keras!

#### Understanding your classification data

Now you will start modeling with a new dataset for a classification problem. This data includes information about passengers on the Titanic.

You will use predictors such as

age

,

fare

and where each passenger embarked from to predict who will survive. This data is from

a tutorial on data science competitions

. Look

here

for descriptions of the features.

df.head(3)

survived pclass ... embarked_from_queenstown embarked_from_southampton

0 0 3 ... 0 1

1 1 1 ... 0 0

2 1 3 ... 0 1

[3 rows x 11 columns]

df.columns

Index(['survived', 'pclass', 'age', 'sibsp', 'parch', 'fare', 'male',

'age_was_missing', 'embarked_from_cherbourg',

'embarked_from_queenstown', 'embarked_from_southampton'],

dtype='object')

#### Last steps in classification models

You’ll now create a classification model using the titanic dataset.

Here, you’ll use the

'sgd'

optimizer, which stands for

Stochastic Gradient Descent

. You’ll now create a classification model using the titanic dataset.

# Import necessary modules

import keras

from keras.layers import Dense

from keras.models import Sequential

from keras.utils import to_categorical

# Convert the target to categorical: target

target = to_categorical(df.survived)

# Set up the model

model = Sequential()

# Add the first layer

model.add(Dense(32, activation='relu', input_shape=(n_cols,)))

# Add the output layer

model.add(Dense(2, activation='softmax'))

# Compile the model

model.compile(optimizer='sgd', loss='categorical_crossentropy', metrics=['accuracy'])

# Fit the model

model.fit(predictors, target)

Epoch 1/10

32/891 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 7.6250 - acc: 0.2188

576/891 [==================>...........] - ETA: 0s - loss: 2.6143 - acc: 0.6024

891/891 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 2.5170 - acc: 0.5948

...

Epoch 10/10

32/891 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.4892 - acc: 0.7500

736/891 [=======================>......] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.6318 - acc: 0.6807

891/891 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 0.6444 - acc: 0.6779

This simple model is generating an accuracy of 68!

#### Making predictions

In this exercise, your predictions will be probabilities, which is the most common way for data scientists to communicate their predictions to colleagues.

# Specify, compile, and fit the model

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(32, activation='relu', input_shape = (n_cols,)))

model.add(Dense(2, activation='softmax'))

model.compile(optimizer='sgd',

loss='categorical_crossentropy',

metrics=['accuracy'])

model.fit(predictors, target)

# Calculate predictions: predictions

predictions = model.predict(pred_data)

# Calculate predicted probability of survival: predicted_prob_true

predicted_prob_true = predictions[:,1]

# print predicted_prob_true

print(predicted_prob_true)

predicted_prob_true

array([0.20054096, 0.3806974 , 0.6795431 , 0.45789802, 0.16493829,

...

0.12394663], dtype=float32)

You’re now ready to begin learning how to fine-tune your models.

#### Diagnosing optimization problems

All of the following could prevent a model from showing an improved loss in its first few epochs.

#### Changing optimization parameters

It’s time to get your hands dirty with optimization. You’ll now try optimizing a model at a very low learning rate, a very high learning rate, and a “just right” learning rate.

You’ll want to look at the results after running this exercise, remembering that a low value for the loss function is good.

For these exercises, we’ve pre-loaded the predictors and target values from your previous classification models (predicting who would survive on the Titanic).

You’ll want the optimization to start from scratch every time you change the learning rate, to give a fair comparison of how each learning rate did in your results. So we have created a function

get_new_model()

that creates an unoptimized model to optimize.

# Import the SGD optimizer

from keras.optimizers import SGD

# Create list of learning rates: lr_to_test

lr_to_test = [0.000001, 0.01, 1]

# Loop over learning rates

for lr in lr_to_test:

print('\n\nTesting model with learning rate: %f\n'%lr )

# Build new model to test, unaffected by previous models

model = get_new_model()

# Create SGD optimizer with specified learning rate: my_optimizer

my_optimizer = SGD(lr=lr)

# Compile the model

model.compile(optimizer=my_optimizer, loss='categorical_crossentropy')

# Fit the model

model.fit(predictors, target)

Testing model with learning rate: 0.000001

Epoch 1/10

32/891 [>.............................] - ETA: 1s - loss: 3.6053

640/891 [====================>.........] - ETA: 0s - loss: 1.9211

891/891 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 1.6579

...

Epoch 10/10

32/891 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.5917

672/891 [=====================>........] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.5966

891/891 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 0.6034

Testing model with learning rate: 0.010000

Epoch 1/10

32/891 [>.............................] - ETA: 1s - loss: 1.0910

576/891 [==================>...........] - ETA: 0s - loss: 1.8064

891/891 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 1.4091

...

Epoch 10/10

32/891 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.6419

672/891 [=====================>........] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.5787

891/891 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 0.5823

Testing model with learning rate: 1.000000

Epoch 1/10

32/891 [>.............................] - ETA: 1s - loss: 1.0273

608/891 [===================>..........] - ETA: 0s - loss: 1.9649

891/891 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 1.8966

...

Epoch 10/10

32/891 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.7226

672/891 [=====================>........] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.6031

891/891 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 0.6060

#### Evaluating model accuracy on validation dataset

Now it’s your turn to monitor model accuracy with a validation data set. A model definition has been provided as

model

. Your job is to add the code to compile it and then fit it. You’ll check the validation score in each epoch.

# Save the number of columns in predictors: n_cols

n_cols = predictors.shape[1]

input_shape = (n_cols,)

# Specify the model

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(100, activation='relu', input_shape = input_shape))

model.add(Dense(100, activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(2, activation='softmax'))

# Compile the model

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='categorical_crossentropy', metrics=['accuracy'])

# Fit the model

hist = model.fit(predictors, target, validation_split=0.3)

Train on 623 samples, validate on 268 samples

Epoch 1/10

32/623 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 3.3028 - acc: 0.4062

608/623 [============================>.] - ETA: 0s - loss: 1.3320 - acc: 0.5938

623/623 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 1.3096 - acc: 0.6003 - val_loss: 0.6805 - val_acc: 0.7201

...

Epoch 10/10

32/623 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.4873 - acc: 0.7812

320/623 [==============>...............] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.5953 - acc: 0.7063

623/623 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 0.6169 - acc: 0.6870 - val_loss: 0.5339 - val_acc: 0.7351

#### Early stopping: Optimizing the optimization

Now that you know how to monitor your model performance throughout optimization, you can use early stopping to stop optimization when it isn’t helping any more. Since the optimization stops automatically when it isn’t helping, you can also set a high value for

epochs

in your call to

.fit()

.

# Import EarlyStopping

from keras.callbacks import EarlyStopping

# Save the number of columns in predictors: n_cols

n_cols = predictors.shape[1]

input_shape = (n_cols,)

# Specify the model

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(100, activation='relu', input_shape = input_shape))

model.add(Dense(100, activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(2, activation='softmax'))

# Compile the model

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='categorical_crossentropy', metrics=['accuracy'])

# Define early_stopping_monitor

early_stopping_monitor = EarlyStopping(patience=2)

# Fit the model

model.fit(predictors, target, epochs=30, validation_split=0.3, callbacks=[early_stopping_monitor])

Train on 623 samples, validate on 268 samples

Epoch 1/30

32/623 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 5.6563 - acc: 0.4688

608/623 [============================>.] - ETA: 0s - loss: 1.6536 - acc: 0.5609

623/623 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 1.6406 - acc: 0.5650 - val_loss: 1.0856 - val_acc: 0.6567

...

Epoch 6/30

32/623 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.4607 - acc: 0.7812

608/623 [============================>.] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.6208 - acc: 0.7007

623/623 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 0.6231 - acc: 0.6982 - val_loss: 0.6149 - val_acc: 0.6828

Epoch 7/30

32/623 [>.............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.6697 - acc: 0.6875

608/623 [============================>.] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.6483 - acc: 0.7072

623/623 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 0.6488 - acc: 0.7063 - val_loss: 0.7276 - val_acc: 0.6493

Because optimization will automatically stop when it is no longer helpful, it is okay to specify the maximum number of epochs as 30 rather than using the default of 10 that you’ve used so far. Here, it seems like the optimization stopped after 7 epochs.

#### Experimenting with wider networks

Now you know everything you need to begin experimenting with different models!

A model called

model_1

has been pre-loaded. You can see a summary of this model printed in the IPython Shell. This is a relatively small network, with only 10 units in each hidden layer.

In this exercise you’ll create a new model called

model_2

which is similar to

model_1

, except it has 100 units in each hidden layer.

# Define early_stopping_monitor

early_stopping_monitor = EarlyStopping(patience=2)

# Create the new model: model_2

model_2 = Sequential()

# Add the first and second layers

model_2.add(Dense(100, activation='relu', input_shape=input_shape))

model_2.add(Dense(100, activation='relu'))

# Add the output layer

model_2.add(Dense(2, activation='softmax'))

# Compile model_2

model_2.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='categorical_crossentropy', metrics=['accuracy'])

# Fit model_1

model_1_training = model_1.fit(predictors, target, epochs=15, validation_split=0.2, callbacks=[early_stopping_monitor], verbose=False)

# Fit model_2

model_2_training = model_2.fit(predictors, target, epochs=15, validation_split=0.2, callbacks=[early_stopping_monitor], verbose=False)

# Create the plot

plt.plot(model_1_training.history['val_loss'], 'r', model_2_training.history['val_loss'], 'b')

plt.xlabel('Epochs')

plt.ylabel('Validation score')

plt.show()

model_1.summary()

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

dense_1 (Dense) (None, 10) 110

_________________________________________________________________

dense_2 (Dense) (None, 10) 110

_________________________________________________________________

dense_3 (Dense) (None, 2) 22

=================================================================

Total params: 242.0

Trainable params: 242

Non-trainable params: 0.0

_________________________________________________________________

model_2.summary()

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

dense_4 (Dense) (None, 100) 1100

_________________________________________________________________

dense_5 (Dense) (None, 100) 10100

_________________________________________________________________

dense_6 (Dense) (None, 2) 202

=================================================================

Total params: 11,402.0

Trainable params: 11,402

Non-trainable params: 0.0

_________________________________________________________________

The blue model is the one you made, the red is the original model. Your model had a lower loss value, so it is the better model.

#### Adding layers to a network

You’ve seen how to experiment with wider networks. In this exercise, you’ll try a deeper network (more hidden layers).

# The input shape to use in the first hidden layer

input_shape = (n_cols,)

# Create the new model: model_2

model_2 = Sequential()

# Add the first, second, and third hidden layers

model_2.add(Dense(50, activation='relu', input_shape=input_shape))

model_2.add(Dense(50, activation='relu'))

model_2.add(Dense(50, activation='relu'))

# Add the output layer

model_2.add(Dense(2, activation='softmax'))

# Compile model_2

model_2.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='categorical_crossentropy', metrics=['accuracy'])

# Fit model 1

model_1_training = model_1.fit(predictors, target, epochs=20, validation_split=0.4, callbacks=[early_stopping_monitor], verbose=False)

# Fit model 2

model_2_training = model_2.fit(predictors, target, epochs=20, validation_split=0.4, callbacks=[early_stopping_monitor], verbose=False)

# Create the plot

plt.plot(model_1_training.history['val_loss'], 'r', model_2_training.history['val_loss'], 'b')

plt.xlabel('Epochs')

plt.ylabel('Validation score')

plt.show()

model_1.summary()

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

dense_1 (Dense) (None, 50) 550

_________________________________________________________________

dense_2 (Dense) (None, 2) 102

=================================================================

Total params: 652.0

Trainable params: 652

Non-trainable params: 0.0

_________________________________________________________________

model_2.summary()

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

dense_3 (Dense) (None, 50) 550

_________________________________________________________________

dense_4 (Dense) (None, 50) 2550

_________________________________________________________________

dense_5 (Dense) (None, 50) 2550

_________________________________________________________________

dense_6 (Dense) (None, 2) 102

=================================================================

Total params: 5,752.0

Trainable params: 5,752

Non-trainable params: 0.0

_________________________________________________________________

#### Experimenting with model structures

You’ve just run an experiment where you compared two networks that were identical except that the 2nd network had an extra hidden layer.

You see that this 2nd network (the deeper network) had better performance. Given that, How to get an even better performance?

Increasing the number of units in each hidden layer would be a good next step to try achieving even better performance.

#### Building your own digit recognition model

You’ve reached the final exercise of the course – you now know everything you need to build an accurate model to recognize handwritten digits!

To add an extra challenge, we’ve loaded only 2500 images, rather than 60000 which you will see in some published results. Deep learning models perform better with more data, however, they also take longer to train, especially when they start becoming more complex.

If you have a computer with a CUDA compatible GPU, you can take advantage of it to improve computation time. If you don’t have a GPU, no problem! You can set up a deep learning environment in the cloud that can run your models on a GPU. Here is a blog post by Dan that explains how to do this – check it out after completing this exercise! It is a great next step as you continue your deep learning journey.

Ready to take your deep learning to the next level? Check out Advanced Deep Learning with Keras in Python to see how the Keras functional API lets you build domain knowledge to solve new types of problems. Once you know how to use the functional API, take a look at “Convolutional Neural Networks for Image Processing” to learn image-specific applications of Keras.

# feature of 28 * 28 = 784 image of a handwriting digit image.

# each value is a number between 0 ~ 255, stands for the darkness of that pixel

X

array([[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

...,

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.]], dtype=float32)

X.shape

(2500, 784)

# target: 0 ~ 9

y

array([[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 1., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

...,

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 1., 0.],

[0., 1., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.]])

y.shape

(2500, 10)

# Create the model: model

model = Sequential()

# Add the first hidden layer

model.add(Dense(50, activation='relu', input_shape=(X.shape[1],)))

# Add the second hidden layer

model.add(Dense(50, activation='relu'))

# Add the output layer

model.add(Dense(y.shape[1], activation='softmax'))

# Compile the model

model.compile(optimizer='adam', loss='categorical_crossentropy', metrics=['accuracy'])

# Fit the model

model.fit(X, y, validation_split=0.3)

Train on 1750 samples, validate on 750 samples

Epoch 1/10

32/1750 [..............................] - ETA: 3s - loss: 2.1979 - acc: 0.2188

480/1750 [=======>......................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 2.1655 - acc: 0.2333

960/1750 [===============>..............] - ETA: 0s - loss: 1.9699 - acc: 0.3354

1440/1750 [=======================>......] - ETA: 0s - loss: 1.7895 - acc: 0.4153

1750/1750 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 1.6672 - acc: 0.4737 - val_loss: 1.0023 - val_acc: 0.7707

...

Epoch 10/10

32/1750 [..............................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.1482 - acc: 1.0000

480/1750 [=======>......................] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.1109 - acc: 0.9792

960/1750 [===============>..............] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.1046 - acc: 0.9812

1440/1750 [=======================>......] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.1028 - acc: 0.9812

1696/1750 [============================>.] - ETA: 0s - loss: 0.1014 - acc: 0.9817

1750/1750 [==============================] - 0s - loss: 0.0999 - acc: 0.9823 - val_loss: 0.3186 - val_acc: 0.9053

You’ve done something pretty amazing. You should see better than 90% accuracy recognizing handwritten digits, even while using a small training set of only 1750 images!

The End.

Thank you for reading.