This is the memo of the 7th course (23 courses in all) of ‘Machine Learning Scientist with Python’ skill track. You can find the original course HERE.

High-dimensional datasets can be overwhelming and leave you not knowing where to start. Typically, you’d visually explore a new dataset first, but when you have too many dimensions the classical approaches will seem insufficient. Fortunately, there are visualization techniques designed specifically for high-dimensional data and you’ll be introduced to these in this course. After exploring the data, you’ll often find that many features hold little information because they don’t show any variance or because they are duplicates of other features. You’ll learn how to detect these features and drop them from the dataset so that you can focus on the informative ones. In a next step, you might want to build a model on these features, and it may turn out that some don’t have any effect on the thing you’re trying to predict. You’ll learn how to detect and drop these irrelevant features too, in order to reduce dimensionality and thus complexity. Finally, you’ll learn how feature extraction techniques can reduce dimensionality for you through the calculation of uncorrelated principal components.

Feature extraction

Exploring high dimensional data

You’ll be introduced to the concept of dimensionality reduction and will learn when an why this is important. You’ll learn the difference between feature selection and feature extraction and will apply both techniques for data exploration. The chapter ends with a lesson on t-SNE, a powerful feature extraction technique that will allow you to visualize a high-dimensional dataset.

Feature selection I, selecting for feature information

In this first out of two chapters on feature selection, you’ll learn about the curse of dimensionality and how dimensionality reduction can help you overcome it. You’ll be introduced to a number of techniques to detect and remove features that bring little added value to the dataset. Either because they have little variance, too many missing values, or because they are strongly correlated to other features.

Feature selection II, selecting for model accuracy

In this second chapter on feature selection, you’ll learn how to let models help you find the most important features in a dataset for predicting a particular target feature. In the final lesson of this chapter, you’ll combine the advice of multiple, different, models to decide on which features are worth keeping.

Feature extraction

This chapter is a deep-dive on the most frequently used dimensionality reduction algorithm, Principal Component Analysis (PCA). You’ll build intuition on how and why this algorithm is so powerful and will apply it both for data exploration and data pre-processing in a modeling pipeline. You’ll end with a cool image compression use case.

You’ll be introduced to the concept of dimensionality reduction and will learn when an why this is important. You’ll learn the difference between feature selection and feature extraction and will apply both techniques for data exploration. The chapter ends with a lesson on t-SNE, a powerful feature extraction technique that will allow you to visualize a high-dimensional dataset.

1.1.1 Finding the number of dimensions in a dataset

A larger sample of the Pokemon dataset has been loaded for you as the Pandas dataframe pokemon_df.

How many dimensions, or columns are in this dataset?

| 12 | pokemon_df.shape(160, 7) |

| :— | :— |

1.1.2 Removing features without variance

A sample of the Pokemon dataset has been loaded as pokemon_df. To get an idea of which features have little variance you should use the IPython Shell to calculate summary statistics on this sample. Then adjust the code to create a smaller, easier to understand, dataset.

| 12345678910 | pokemon_df.describe() HP Attack Defense Generationcount 160.00000 160.00000 160.000000 160.0mean 64.61250 74.98125 70.175000 1.0std 27.92127 29.18009 28.883533 0.0min 10.00000 5.00000 5.000000 1.025% 45.00000 52.00000 50.000000 1.050% 60.00000 71.00000 65.000000 1.075% 80.00000 95.00000 85.000000 1.0max 250.00000 155.00000 180.000000 1.0 |

| :— | :— |

| 123456 | pokemon_df.describe(exclude='number') Name Type Legendarycount 160 160 160unique 160 15 1top Weepinbell Water Falsefreq 1 31 160 |

| :— | :— |

| 1234567891011 | # Leave this list as isnumber_cols = ['HP', 'Attack', 'Defense'] # Remove the feature without variance from this listnon_number_cols = ['Name', 'Type'] # Create a new dataframe by subselecting the chosen featuresdf_selected = pokemon_df[number_cols + non_number_cols] # Prints the first 5 lines of the new dataframeprint(df_selected.head()) |

| :— | :— |

| 123456 | HP Attack Defense Name Type0 45 49 49 Bulbasaur Grass1 60 62 63 Ivysaur Grass2 80 82 83 Venusaur Grass3 80 100 123 VenusaurMega Venusaur Grass4 39 52 43 Charmander Fire |

| :— | :— |

1.2.1 Visually detecting redundant features

Data visualization is a crucial step in any data exploration. Let’s use Seaborn to explore some samples of the US Army ANSUR body measurement dataset.

Two data samples have been pre-loaded as ansur_df_1 and ansur_df_2.

Seaborn has been imported as sns.

| 12345 | # Create a pairplot and color the points using the 'Gender' featuresns.pairplot(ansur_df_1, hue='Gender', diag_kind='hist') # Show the plotplt.show() |

| :— | :— |

| 12345678 | # Remove one of the redundant featuresreduced_df = ansur_df_1.drop('stature_m', axis=1) # Create a pairplot and color the points using the 'Gender' featuresns.pairplot(reduced_df, hue='Gender') # Show the plotplt.show() |

| :— | :— |

| 123456 | # Create a pairplot and color the points using the 'Gender' featuresns.pairplot(ansur_df_2, hue='Gender', diag_kind='hist') # Show the plotplt.show() |

| :— | :— |

| 12345678 | # Remove the redundant featurereduced_df = ansur_df_2.drop('n_legs', axis=1) # Create a pairplot and color the points using the 'Gender' featuresns.pairplot(reduced_df, hue='Gender', diag_kind='hist') # Show the plotplt.show() |

| :— | :— |

The body height (inches) and stature (meters) hold the same information in a different unit + all the individuals in the second sample have two legs.

1.2.2 Advantage of feature selection

What advantage does feature selection have over feature extraction?

The selected features remain unchanged, and are therefore easy to interpret.

1.3.1 t-SNE intuition

t-SNE is super powerful, but do you know exactly when to use it?

When you want to visually explore the patterns in a high dimensional dataset.

1.3.2 Fitting t-SNE to the ANSUR data

t-SNE is a great technique for visual exploration of high dimensional datasets. In this exercise, you’ll apply it to the ANSUR dataset. You’ll remove non-numeric columns from the pre-loaded dataset df and fit TSNE to his numeric dataset.

| 12345678910111213141516 | # Non-numerical columns in the datasetnon_numeric = ['Branch', 'Gender', 'Component'] # Drop the non-numerical columns from dfdf_numeric = df.drop(non_numeric, axis=1) # Create a t-SNE model with learning rate 50m = TSNE(learning_rate=50) # Fit and transform the t-SNE model on the numeric datasettsne_features = m.fit_transform(df_numeric)print(tsne_features.shape)(6068, 2) df.shape(6068, 94) |

| :— | :— |

1.3.3 t-SNE visualisation of dimensionality

Time to look at the results of your hard work. In this exercise, you will visualize the output of t-SNE dimensionality reduction on the combined male and female Ansur dataset. You’ll create 3 scatterplots of the 2 t-SNE features ('x' and 'y') which were added to the dataset df. In each scatterplot you’ll color the points according to a different categorical variable.

seaborn has already been imported as sns and matplotlib.pyplot as plt.

| 12345 | # Color the points according to Army Componentsns.scatterplot(x="x", y="y", hue='Component', data=df) # Show the plotplt.show() |

| :— | :— |

| 12345 | # Color the points by Army Branchsns.scatterplot(x="x", y="y", hue='Branch', data=df) # Show the plotplt.show() |

| :— | :— |

| 12345 | # Color the points by Gendersns.scatterplot(x="x", y="y", hue='Gender', data=df) # Show the plotplt.show() |

| :— | :— |

There is a Male and a Female cluster. t-SNE found these gender differences in body shape without being told about them explicitly! From the second plot you learned there are more males in the Combat Arms Branch.

2.1.1 Train – test split

In this chapter, you will keep working with the ANSUR dataset. Before you can build a model on your dataset, you should first decide on which feature you want to predict. In this case, you’re trying to predict gender.

You need to extract the column holding this feature from the dataset and then split the data into a training and test set. The training set will be used to train the model and the test set will be used to check its performance on unseen data.

ansur_df has been pre-loaded for you.

| 1234567891011121314 | # Import train_test_split()from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split # Select the Gender column as the feature to be predicted (y)y = ansur_df['Gender'] # Remove the Gender column to create the training dataX = ansur_df.drop('Gender', axis=1) # Perform a 70% train and 30% test data splitX_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3) print("{} rows in test set vs. {} in training set. {} Features.".format(X_test.shape[0], X_train.shape[0], X_test.shape[1]))# 300 rows in test set vs. 700 in training set. 91 Features. |

| :— | :— |

2.1.2 Fitting and testing the model

In the previous exercise, you split the dataset into X_train, X_test, y_train, and y_test. These datasets have been pre-loaded for you. You’ll now create a support vector machine classifier model (SVC()) and fit that to the training data. You’ll then calculate the accuracy on both the test and training set to detect overfitting.

| 12345678910111213141516 | # Import SVC from sklearn.svm and accuracy_score from sklearn.metricsfrom sklearn.svm import SVCfrom sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score # Create an instance of the Support Vector Classification classsvc = SVC() # Fit the model to the training datasvc.fit(X_train, y_train) # Calculate accuracy scores on both train and test dataaccuracy_train = accuracy_score(y_train, svc.predict(X_train))accuracy_test = accuracy_score(y_test, svc.predict(X_test)) print("{0:.1%} accuracy on test set vs. {1:.1%} on training set".format(accuracy_test, accuracy_train))# 49.7% accuracy on test set vs. 100.0% on training set |

| :— | :— |

Looks like the model badly overfits on the training data. On unseen data it performs worse than a random selector would.

2.1.3 Accuracy after dimensionality reduction

You’ll reduce the overfit with the help of dimensionality reduction. In this case, you’ll apply a rather drastic form of dimensionality reduction by only selecting a single column that has some good information to distinguish between genders. You’ll repeat the train-test split, model fit and prediction steps to compare the accuracy on test vs. training data.

| 1234567891011121314 | # Assign just the 'neckcircumferencebase' column from ansur_df to XX = ansur_df[['neckcircumferencebase']] # Split the data, instantiate a classifier and fit the dataX_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3)svc = SVC()svc.fit(X_train, y_train) # Calculate accuracy scores on both train and test dataaccuracy_train = accuracy_score(y_train, svc.predict(X_train))accuracy_test = accuracy_score(y_test, svc.predict(X_test)) print("{0:.1%} accuracy on test set vs. {1:.1%} on training set".format(accuracy_test, accuracy_train))# 93.3% accuracy on test set vs. 94.9% on training set |

| :— | :— |

Wow, what just happened!? On the full dataset the model is rubbish but with a single feature we can make good predictions? This is an example of the curse of dimensionality! The model badly overfits when we feed it too many features. It overlooks that neck circumference by itself is pretty different for males and females.

2.2.1 Finding a good variance threshold

You’ll be working on a slightly modified subsample of the ANSUR dataset with just head measurements pre-loaded as head_df.

| 1234 | # Create the boxplothead_df.boxplot() plt.show() |

| :— | :— |

| 12345 | # Normalize the datanormalized_df = head_df / head_df.mean() normalized_df.boxplot()plt.show() |

| :— | :— |

| 12345 | # Normalize the datanormalized_df = head_df / head_df.mean() # Print the variances of the normalized dataprint(normalized_df.var()) |

| :— | :— |

| 1234567 | headbreadth 1.678952e-03headcircumference 1.029623e-03headlength 1.867872e-03tragiontopofhead 2.639840e-03n_hairs 1.002552e-08measurement_error 3.231707e-27dtype: float64 |

| :— | :— |

Inspect the printed variances. If you want to remove the 2 very low variance features. What would be a good variance threshold?

1.0e-03

2.2.2 Features with low variance

In the previous exercise you established that 0.001 is a good threshold to filter out low variance features in head_df after normalization. Now use the VarianceThreshold feature selector to remove these features.

| 12345678910111213141516 | from sklearn.feature_selection import VarianceThreshold # Create a VarianceThreshold feature selectorsel = VarianceThreshold(threshold=10**-3) # Fit the selector to normalized head_dfsel.fit(head_df / head_df.mean()) # Create a boolean maskmask = sel.get_support() # Apply the mask to create a reduced dataframereduced_df = head_df.loc[:, mask] print("Dimensionality reduced from {} to {}.".format(head_df.shape[1], reduced_df.shape[1]))# Dimensionality reduced from 6 to 4. |

| :— | :— |

2.2.3 Removing features with many missing values

You’ll apply feature selection on the Boston Public Schools dataset which has been pre-loaded as school_df. Calculate the missing value ratio per feature and then create a mask to remove features with many missing values.

| 1234567891011121314151617181920212223 | school_df.isna().sum() / len(school_df)x 0.000000y 0.000000objectid_1 0.000000objectid 0.000000bldg_id 0.000000bldg_name 0.000000address 0.000000city 0.000000zipcode 0.000000csp_sch_id 0.000000sch_id 0.000000sch_name 0.000000sch_label 0.000000sch_type 0.000000shared 0.877863complex 0.984733label 0.000000tlt 0.000000pl 0.000000point_x 0.000000point_y 0.000000dtype: float64 |

| :— | :— |

| 12345678910 | # Create a boolean mask on whether each feature less than 50% missing values.mask = school_df.isna().sum() / len(school_df) < 0.5 # Create a reduced dataset by applying the maskreduced_df = school_df.loc[:,mask] print(school_df.shape)print(reduced_df.shape)# (131, 21)# (131, 19) |

| :— | :— |

2.3.1 Correlation intuition

The correlation coefficient of A to B is equal to that of B to A.

2.3.2 Inspecting the correlation matrix

A sample of the ANSUR body measurements dataset has been pre-loaded as ansur_df. Use the terminal to create a correlation matrix for this dataset.

What is the correlation coefficient between wrist and ankle circumference?

| 1234567 | ansur_df.corr() Elbow rest height Wrist circumference Ankle circumference Buttock height Crotch heightElbow rest height 1.000000 0.294753 0.301963 -0.007013 -0.026090Wrist circumference 0.294753 1.000000 0.702178 0.576679 0.606582Ankle circumference 0.301963 0.702178 1.000000 0.367548 0.386502Buttock height -0.007013 0.576679 0.367548 1.000000 0.929411Crotch height -0.026090 0.606582 0.386502 0.929411 1.000000 |

| :— | :— |

0.702178

2.3.3 Visualizing the correlation matrix

Reading the correlation matrix of ansur_df in its raw, numeric format doesn’t allow us to get a quick overview. Let’s improve this by removing redundant values and visualizing the matrix using seaborn.

| 123456 | # Create the correlation matrixcorr = ansur_df.corr() # Draw the heatmapsns.heatmap(corr, cmap=cmap, center=0, linewidths=1, annot=True, fmt=".2f")plt.show() |

| :— | :— |

| 123456789 | # Create the correlation matrixcorr = ansur_df.corr() # Generate a mask for the upper trianglemask = np.triu(np.ones_like(corr, dtype=bool)) # Add the mask to the heatmapsns.heatmap(corr, mask=mask, cmap=cmap, center=0, linewidths=1, annot=True, fmt=".2f")plt.show() |

| :— | :— |

2.4.1 Filtering out highly correlated features

You’re going to automate the removal of highly correlated features in the numeric ANSUR dataset. You’ll calculate the correlation matrix and filter out columns that have a correlation coefficient of more than 0.95 or less than -0.95.

Since each correlation coefficient occurs twice in the matrix (correlation of A to B equals correlation of B to A) you’ll want to ignore half of the correlation matrix so that only one of the two correlated features is removed. Use a mask trick for this purpose.

| 123456789101112131415 | # Calculate the correlation matrix and take the absolute valuecorr_matrix = ansur_df.corr().abs() # Create a True/False mask and apply itmask = np.triu(np.ones_like(corr_matrix, dtype=bool))tri_df = corr_matrix.mask(mask) # List column names of highly correlated features (r > 0.95)to_drop = [c for c in tri_df.columns if any(tri_df[c] > 0.95)] # Drop the features in the to_drop listreduced_df = ansur_df.drop(to_drop, axis=1) print("The reduced dataframe has {} columns.".format(reduced_df.shape[1]))# The reduced dataframe has 88 columns. |

| :— | :— |

You’ve automated the removal of highly correlated features.

2.4.2 Nuclear energy and pool drownings

The dataset that has been pre-loaded for you as weird_df contains actual data provided by the US Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and Department of Energy.

Let’s see if we can find a pattern.

| 123 | # Put nuclear energy production on the x-axis and the number of pool drownings on the y-axissns.scatterplot(x='nuclear_energy', y='pool_drownings', data=weird_df)plt.show() |

| :— | :— |

| 12 | # Print out the correlation matrix of weird_dfprint(weird_df.corr()) |

| :— | :— |

| 123 | pool_drownings nuclear_energypool_drownings 1.000000 0.901179nuclear_energy 0.901179 1.000000 |

| :— | :— |

What can you conclude from the strong correlation (r=0.9) between these features? Not much, correlation does not imply causation.

3.1.1 Building a diabetes classifier

You’ll be using the Pima Indians diabetes dataset to predict whether a person has diabetes using logistic regression. There are 8 features and one target in this dataset. The data has been split into a training and test set and pre-loaded for you as X_train, y_train, X_test, and y_test.

A StandardScaler() instance has been predefined as scaler and a LogisticRegression() one as lr.

| 123456789101112131415 | # Fit the scaler on the training features and transform these in one goX_train_std = scaler.fit_transform(X_train) # Fit the logistic regression model on the scaled training datalr.fit(X_train_std, y_train) # Scale the test featuresX_test_std = scaler.transform(X_test) # Predict diabetes presence on the scaled test sety_pred = lr.predict(X_test_std) # Prints accuracy metrics and feature coefficientsprint("{0:.1%} accuracy on test set.".format(accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)))print(dict(zip(X.columns, abs(lr.coef_[0]).round(2)))) |

| :— | :— |

| 12 | 79.6% accuracy on test set.{'family': 0.34, 'diastolic': 0.03, 'glucose': 1.23, 'triceps': 0.24, 'age': 0.34, 'insulin': 0.19, 'bmi': 0.38, 'pregnant': 0.04} |

| :— | :— |

3.1.2 Manual Recursive Feature Elimination

Now that we’ve created a diabetes classifier, let’s see if we can reduce the number of features without hurting the model accuracy too much.

On the second line of code the features are selected from the original dataframe. Adjust this selection.

A StandardScaler() instance has been predefined as scaler and a LogisticRegression() one as lr.

| 12345 | # Remove the feature with the lowest model coefficientX = diabetes_df[['pregnant', 'glucose', 'triceps', 'insulin', 'bmi', 'family', 'age']] 80.6% accuracy on test set.{'family': 0.34, 'glucose': 1.23, 'triceps': 0.24, 'age': 0.35, 'insulin': 0.2, 'bmi': 0.39, 'pregnant': 0.05} |

| :— | :— |

| 12345 | # Remove the 2 features with the lowest model coefficientsX = diabetes_df[['glucose', 'triceps', 'bmi', 'family', 'age']] 79.6% accuracy on test set.{'family': 0.34, 'age': 0.37, 'bmi': 0.34, 'glucose': 1.13, 'triceps': 0.25} |

| :— | :— |

| 12345 | # Only keep the feature with the highest coefficientX = diabetes_df[['glucose']] 76.5% accuracy on test set.{'glucose': 1.27} |

| :— | :— |

| 12345678910 | # Performs a 25-75% train test splitX_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.25, random_state=0) # Scales features and fits the logistic regression model to the datalr.fit(scaler.fit_transform(X_train), y_train) # Calculates the accuracy on the test set and prints coefficientsacc = accuracy_score(y_test, lr.predict(scaler.transform(X_test)))print("{0:.1%} accuracy on test set.".format(acc))print(dict(zip(X.columns, abs(lr.coef_[0]).round(2)))) |

| :— | :— |

Removing all but one feature only reduced the accuracy by a few percent.

3.1.3 Automatic Recursive Feature Elimination

Now let’s automate this recursive process. Wrap a Recursive Feature Eliminator (RFE) around our logistic regression estimator and pass it the desired number of features.

| 123456789101112131415 | # Create the RFE with a LogisticRegression estimator and 3 features to selectrfe = RFE(estimator=LogisticRegression(), n_features_to_select=3, verbose=1) # Fits the eliminator to the datarfe.fit(X_train, y_train) # Print the features and their ranking (high = dropped early on)print(dict(zip(X.columns, rfe.ranking_))) # Print the features that are not eliminatedprint(X.columns[rfe.support_]) # Calculates the test set accuracyacc = accuracy_score(y_test, rfe.predict(X_test))print("{0:.1%} accuracy on test set.".format(acc)) |

| :— | :— |

| 12345678 | Fitting estimator with 8 features.Fitting estimator with 7 features.Fitting estimator with 6 features.Fitting estimator with 5 features.Fitting estimator with 4 features.{'family': 2, 'diastolic': 6, 'glucose': 1, 'triceps': 3, 'age': 1, 'insulin': 4, 'bmi': 1, 'pregnant': 5}Index(['glucose', 'bmi', 'age'], dtype='object')80.6% accuracy on test set. |

| :— | :— |

When we eliminate all but the 3 most relevant features we get a 80.6% accuracy on the test set.

3.2.1 Building a random forest model

You’ll again work on the Pima Indians dataset to predict whether an individual has diabetes. This time using a random forest classifier. You’ll fit the model on the training data after performing the train-test split and consult the feature importance values.

| 123456789101112131415 | # Perform a 75% training and 25% test data splitX_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.25, random_state=0) # Fit the random forest model to the training datarf = RandomForestClassifier(random_state=0)rf.fit(X_train, y_train) # Calculate the accuracyacc = accuracy_score(y_test, rf.predict(X_test)) # Print the importances per featureprint(dict(zip(X.columns, rf.feature_importances_.round(2)))) # Print accuracyprint("{0:.1%} accuracy on test set.".format(acc)) |

| :— | :— |

| 12 | {'family': 0.12, 'diastolic': 0.08, 'glucose': 0.21, 'triceps': 0.11, 'age': 0.16, 'insulin': 0.13, 'bmi': 0.09, 'pregnant': 0.09}77.6% accuracy on test set. |

| :— | :— |

The random forest model gets 78% accuracy on the test set and 'glucose' is the most important feature (0.21).

3.2.2 Random forest for feature selection

| 123456789 | # Create a mask for features importances above the thresholdmask = rf.feature_importances_ > 0.15 # Apply the mask to the feature dataset Xreduced_X = X.loc[:,mask] # prints out the selected column namesprint(reduced_X.columns)# Index(['glucose', 'age'], dtype='object') |

| :— | :— |

Only the features 'glucose' and 'age' were considered sufficiently important.

3.2.3 Recursive Feature Elimination with random forests

You’ll wrap a Recursive Feature Eliminator around a random forest model to remove features step by step. This method is more conservative compared to selecting features after applying a single importance threshold. Since dropping one feature can influence the relative importances of the others.

| 123456789101112 | # Wrap the feature eliminator around the random forest modelrfe = RFE(estimator=RandomForestClassifier(), n_features_to_select=2, verbose=1) # Fit the model to the training datarfe.fit(X_train, y_train) # Create a mask using an attribute of rfemask = rfe.support_ # Apply the mask to the feature dataset X and print the resultreduced_X = X.loc[:,mask]print(reduced_X.columns) |

| :— | :— |

| 1234567 | Fitting estimator with 8 features.Fitting estimator with 7 features.Fitting estimator with 6 features.Fitting estimator with 5 features.Fitting estimator with 4 features.Fitting estimator with 3 features.Index(['glucose', 'bmi'], dtype='object') |

| :— | :— |

| 123456789101112 | # Set the feature eliminator to remove 2 features on each steprfe = RFE(estimator=RandomForestClassifier(), n_features_to_select=2, step=2, verbose=1) # Fit the model to the training datarfe.fit(X_train, y_train) # Create a maskmask = rfe.support_ # Apply the mask to the feature dataset X and print the resultreduced_X = X.loc[:, mask]print(reduced_X.columns) |

| :— | :— |

| 1234 | Fitting estimator with 8 features.Fitting estimator with 6 features.Fitting estimator with 4 features.Index(['glucose', 'insulin'], dtype='object') |

| :— | :— |

Compared to the quick and dirty single threshold method from the previous exercise one of the selected features is different.

3.3.1 Creating a LASSO regressor

You’ll be working on the numeric ANSUR body measurements dataset to predict a persons Body Mass Index (BMI) using the pre-imported Lasso() regressor. BMI is a metric derived from body height and weight but those two features have been removed from the dataset to give the model a challenge.

You’ll standardize the data first using the StandardScaler() that has been instantiated for you as scaler to make sure all coefficients face a comparable regularizing force trying to bring them down.

| 1234567891011 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

3.3.2 Lasso model results

Now that you’ve trained the Lasso model, you’ll score its predictive capacity (R2) on the test set and count how many features are ignored because their coefficient is reduced to zero.

| 12345678910111213 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 12 | The model can predict 84.7% of the variance in the test set.The model has ignored 82 out of 91 features. |

| :— | :— |

We can predict almost 85% of the variance in the BMI value using just 9 out of 91 of the features. The R^2 could be higher though.

3.3.3 Adjusting the regularization strength

Your current Lasso model has an R2R2 score of 84.7%. When a model applies overly powerful regularization it can suffer from high bias, hurting its predictive power.

Let’s improve the balance between predictive power and model simplicity by tweaking the alpha parameter.

| 1234567891011 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 12 | The model can predict 98.3% of the variance in the test set.64 out of 91 features were ignored. |

| :— | :— |

With this more appropriate regularization strength we can predict 98% of the variance in the BMI value while ignoring 2/3 of the features.

3.4.1 Creating a LassoCV regressor

You’ll be predicting biceps circumference on a subsample of the male ANSUR dataset using the LassoCV() regressor that automatically tunes the regularization strength (alpha value) using Cross-Validation.

| 1234567891011121314 |

|

|---|

| 123 | Optimal alpha = 0.089The model explains 88.2% of the test set variance26 features out of 32 selected |

| :— | :— |

We got a decent R squared and removed 6 features. We’ll save the lcv_mask for later on.

3.4.2 Ensemble models for extra votes

The LassoCV() model selected 26 out of 32 features. Not bad, but not a spectacular dimensionality reduction either. Let’s use two more models to select the 10 features they consider most important using the Recursive Feature Eliminator (RFE).

| 1234567891011121314 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 123456789 | Fitting estimator with 32 features.Fitting estimator with 29 features.Fitting estimator with 26 features.Fitting estimator with 23 features.Fitting estimator with 20 features.Fitting estimator with 17 features.Fitting estimator with 14 features.Fitting estimator with 11 features.The model can explain 85.6% of the variance in the test set |

| :— | :— |

| 1234567891011121314 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 123456789 | Fitting estimator with 32 features.Fitting estimator with 29 features.Fitting estimator with 26 features.Fitting estimator with 23 features.Fitting estimator with 20 features.Fitting estimator with 17 features.Fitting estimator with 14 features.Fitting estimator with 11 features.The model can explain 84.0% of the variance in the test set |

| :— | :— |

Inluding the Lasso linear model from the previous exercise, we now have the votes from 3 models on which features are important.

3.4.3 Combining 3 feature selectors

We’ll combine the votes of the 3 models you built in the previous exercises, to decide which features are important into a meta mask. We’ll then use this mask to reduce dimensionality and see how a simple linear regressor performs on the reduced dataset.

| 123456789101112131415 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

Using the votes from 3 models you were able to select just 7 features that allowed a simple linear model to get a high accuracy!

You want to compare prices for specific products between stores. The features in the pre-loaded dataset sales_df are: storeID, product, quantity and revenue. The quantity and revenue features tell you how many items of a particular product were sold in a store and what the total revenue was. For the purpose of your analysis it’s more interesting to know the average price per product.

| 123456 | storeID product quantity revenue0 A Apples 1811 9300.61 A Bananas 1003 3375.22 A Oranges 1604 8528.53 B Apples 1785 9181.04 B Bananas 944 3680.2 |

| :— | :— |

| 1234567 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 123456 |

|

|---|

When you understand the dataset well, always check if you can calculate relevant features and drop irrelevant ones.

4.1.2 Manual feature extraction II

You’re working on a variant of the ANSUR dataset, height_df, where a person’s height was measured 3 times. Add a feature with the mean height to the dataset and then drop the 3 original features.

| 123456 |

|

|---|

| 1234567 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 123456 |

|

|---|

4.1.3 Principal component intuition

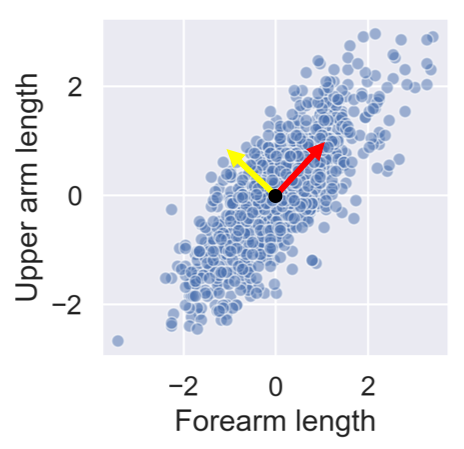

After standardizing the lower and upper arm lengths from the ANSUR dataset we’ve added two perpendicular vectors that are aligned with the main directions of variance. We can describe each point in the dataset as a combination of these two vectors multiplied with a value each. These values are then called principal components.

People with a negative component for the yellow vector have long forearms relative to their upper arms.

4.2.1 Calculating Principal Components

You’ll visually inspect a 4 feature sample of the ANSUR dataset before and after PCA using Seaborn’s pairplot(). This will allow you to inspect the pairwise correlations between the features.

| 1234 |

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 123456789101112131415 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

Notice how, in contrast to the input features, none of the principal components are correlated to one another.

4.2.2 PCA on a larger dataset

You’ll now apply PCA on a somewhat larger ANSUR datasample with 13 dimensions, once again pre-loaded as ansur_df. The fitted model will be used in the next exercise. Since we are not using the principal components themselves there is no need to transform the data, instead, it is sufficient to fit pca to the data.

| 12345678910 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

You’ve fitted PCA on our 13 feature data samples. Now let’s see how the components explain the variance.

4.2.3 PCA explained variance

You’ll be inspecting the variance explained by the different principal components of the pca instance you created in the previous exercise.

| 123456 |

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 123456 |

<code></code> <code></code>

|

|---|

What’s the lowest number of principal components you should keep if you don’t want to lose more than 10% of explained variance during dimensionality reduction? 4 principal components

Using no more than 4 principal components we can explain more than 90% of the variance in the 13 feature dataset.

You’ll apply PCA to the numeric features of the Pokemon dataset, poke_df, using a pipeline to combine the feature scaling and PCA in one go. You’ll then interpret the meanings of the first two components.

| 1234567891011121314 |

<code></code>

|

|---|

PC2: Defense has a strong positive effect on the second component and speed a strong negative one. This component quantifies an agility vs. armor & protection trade-off.

You’ve used the pipeline for the first time and understand how the features relate to the components.

Question

Possible Answers

Sp. Atk has the biggest effect on this feature by far. PC 1 can be interpreted as a measure of how good a Pokemon’s special attack is.****

Question

Possible Answers

4.3.2 PCA for feature exploration

You’ll use the PCA pipeline you’ve built in the previous exercise to visually explore how some categorical features relate to the variance in poke_df. These categorical features (Type & Legendary) can be found in a separate dataframe poke_cat_df.

| 1234567 |

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 12345 |

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 12345678 |

|

|---|

| 123 |

|

|---|

| 1234 |

|

|---|

| 1234 |

|

|---|

Looks like the different types are scattered all over the place while the legendary pokemon always score high for PC 1 meaning they have high stats overall. Their spread along the PC 2 axis tells us they aren’t consistently fast and vulnerable or slow and armored.

4.3.3 PCA in a model pipeline

We just saw that legendary pokemon tend to have higher stats overall. Let’s see if we can add a classifier to our pipeline that detects legendary versus non-legendary pokemon based on the principal components.

The data has been pre-loaded for you and split into training and tests datasets: X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test.

Same goes for all relevant packages and classes(Pipeline(), StandardScaler(), PCA(), RandomForestClassifier()).

| 123456789101112131415 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

<code></code>

|

Looks like adding the third component does not increase the model accuracy, even though it adds information to the dataset.

4.4.1 Selecting the proportion of variance to keep

You’ll let PCA determine the number of components to calculate based on an explained variance threshold that you decide.

| 12345678 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

| 12345 |

|

|---|

We need to more than double the components to go from 80% to 90% explained variance.

Question

Possible Answers

4.4.2 Choosing the number of components

You’ll now make a more informed decision on the number of principal components to reduce your data to using the “elbow in the plot” technique.

| 12345678910111213 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

To how many components can you reduce the dataset without compromising too much on explained variance? Note that the x-axis is zero indexed.

The ‘elbow’ in the plot is at 3 components (the 3rd component has index 2).

Question

Possible Answers

4.4.3 PCA for image compression

You’ll reduce the size of 16 images with hand written digits (MNIST dataset) using PCA.

The samples are 28 by 28 pixel gray scale images that have been flattened to arrays with 784 elements each (28 x 28 = 784) and added to the 2D numpy array X_test. Each of the 784 pixels has a value between 0 and 255 and can be regarded as a feature.

A pipeline with a scaler and PCA model to select 78 components has been pre-loaded for you as pipe. This pipeline has already been fitted to the entire MNIST dataset except for the 16 samples in X_test.

Finally, a function plot_digits has been created for you that will plot 16 images in a grid.

| 12 |

|

|---|

| 1234 | pipePipeline(memory=None, steps=[('scaler', StandardScaler(copy=True, with_mean=True, with_std=True)), ('reducer', PCA(copy=True, iterated_power='auto', n_components=78, random_state=None, svd_solver='auto', tol=0.0, whiten=False))]) |

| :— | :— |

| 12345678910111213141516171819 |

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

<code></code>

|

|---|

You’ve reduced the size of the data 10 fold but were able to reconstruct images with reasonable quality.

Thank you for reading and hope you’ve learned a lot.